In a country grappling with a shadow pandemic of Gender-Based Violence (GBV), the digital landscape of South Africa has recently become a sanctuary for survivors to break their silence.

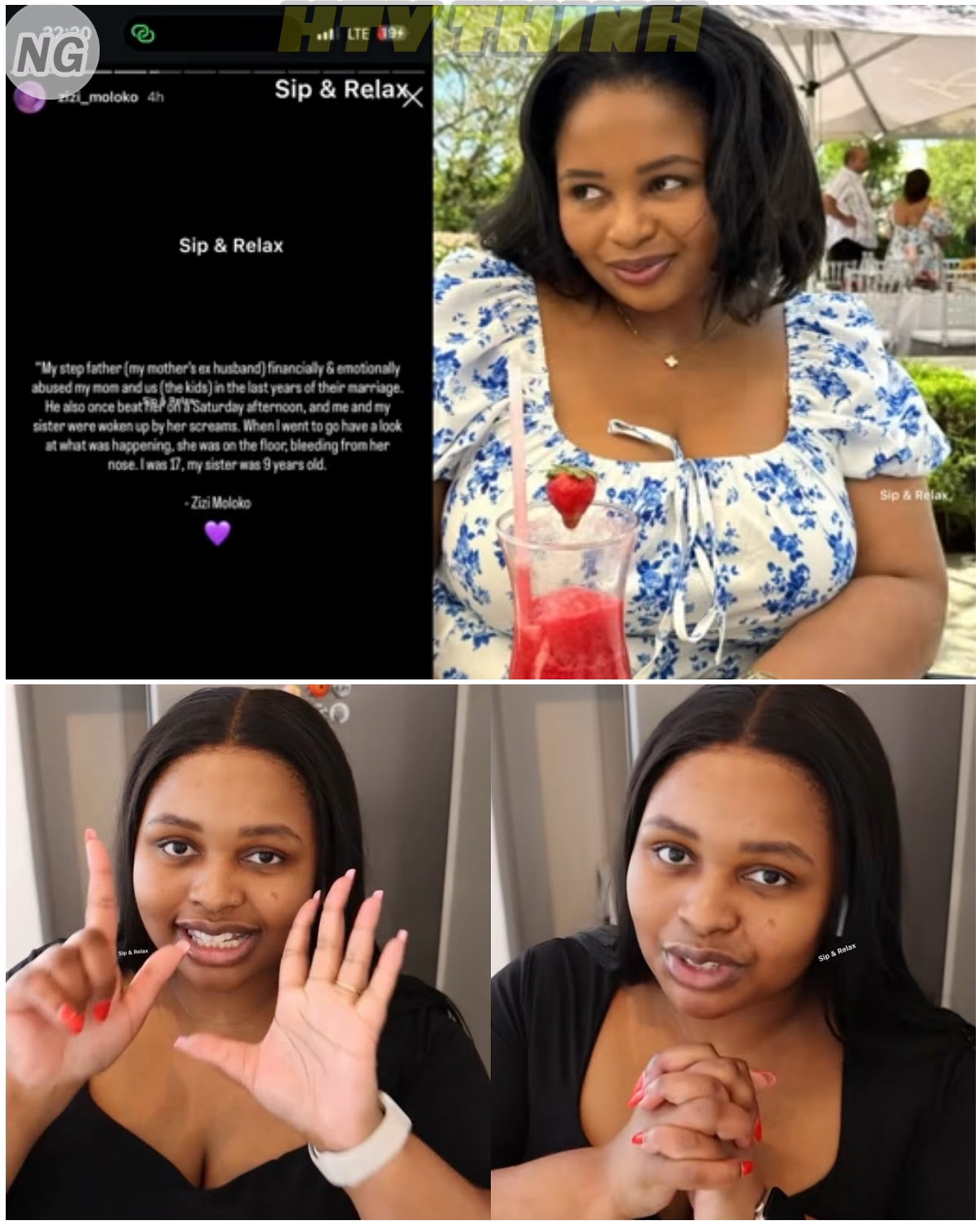

Following a viral social media movement where women changed their profile pictures to purple to raise awareness, influencer Zizi Moloko shared a harrowing account of her personal experiences with violence and abuse.

Her story, shared via Instagram and discussed extensively online, provides a chilling roadmap of the systemic trauma many South African women face from childhood into adulthood.

A Childhood Defined by Domestic Terror

Zizi Moloko’s earliest memories are not of play or comfort, but of witnessing brutal physical violence within her own home.

She revealed that her only memory of her biological father is seeing him beat her mother when she was just five years old and her mother was barely twenty-three.

This cycle of abuse unfortunately continued with her stepfather, who Zizi claims financially and emotionally abused the family throughout her mother’s subsequent marriage.

In one particularly traumatic incident when Zizi was seventeen, she and her nine-year-old sister were awoken on a Saturday afternoon by their mother’s screams.

Upon investigating, Zizi found her mother on the floor, bleeding from her nose—a visceral image that highlights the vulnerability of children living in domestic warzones.

The Normalization of Male Violence

Beyond her immediate household, Zizi described a social environment where violence against women is often bragged about rather than condemned.

She recounted a cousin who openly boasted about hitting a girl at a club because she had “offended” him.

When confronted by his female cousins about how he would feel if someone hit them, the man justified his actions by stating he only hits “loose girls” who are “disrespectful,” implying they deserve the assault.

This rhetoric exposes a dangerous cultural mindset where men feel entitled to physically discipline women based on arbitrary moral judgments.

Zizi further detailed how justice is rarely served, noting that men in her family have repeatedly beaten their partners and that her younger sister was targeted by a groomer who sent her pornography while she was a minor.

University Trauma and Digital Harassment

The violence Zizi experienced followed her into her tertiary education years, illustrating that no space—be it home, school, or university—is inherently safe.

During her first year of varsity, a man she liked tried to force himself onto her in a restroom, ignoring her “no” and telling her to “stop playing hard to get” because “girls like it when we are aggressive”.

Though she fought him off, the incident left a lasting mark on her sense of safety.

In the modern era, this harassment has extended to the digital realm, where Zizi reported receiving unsolicited pictures of genitals from complete strangers on Instagram multiple times over the last few years.

These stories are not isolated incidents but represent a broader pattern of South African men inflicting violence on women and children with near-total impunity.

The Pain of Victim Blaming

One of the most disheartening aspects of the current GBV crisis, as highlighted by Zizi and commentators, is the role of victim-blaming within the community.

Even when women find the courage to speak out, they are often met with interrogations about what they were wearing, where they were going at night, or what they said to provoke the attacker.

This judgment does not only come from men but also from other women, which creates a culture of shame that forces many survivors into silence.

The commentator noted that South Africa is a “violent country” where women are judged even for being assaulted in seemingly “safe” places like churches or schools.

The tragic case of two young women “unalived” in Mamelodi served as a recent example, as the public immediately questioned why they were out late rather than condemning the perpetrator.

A Call for Cultural Change in 2026

As the festive season approaches, the discussion around Zizi Moloko’s story serves as a somber reminder of the work that remains to be done.

The commentator expressed hope that by 2026, the culture of victim-blaming will finally begin to fade and that justice will be sought for the many men who “still walk free” after inflicting violence.

The move toward collective awareness, such as the purple profile picture movement, is a start, but true change requires addressing the underlying attitudes that promote or excuse GBV.

Ultimately, Zizi’s bravery in posting her story “all night long” to get through her list of traumas is a testament to the resilience of South African women.

It is a plea for a society where women can live without the constant threat of being “broken” by those who are supposed to protect them.