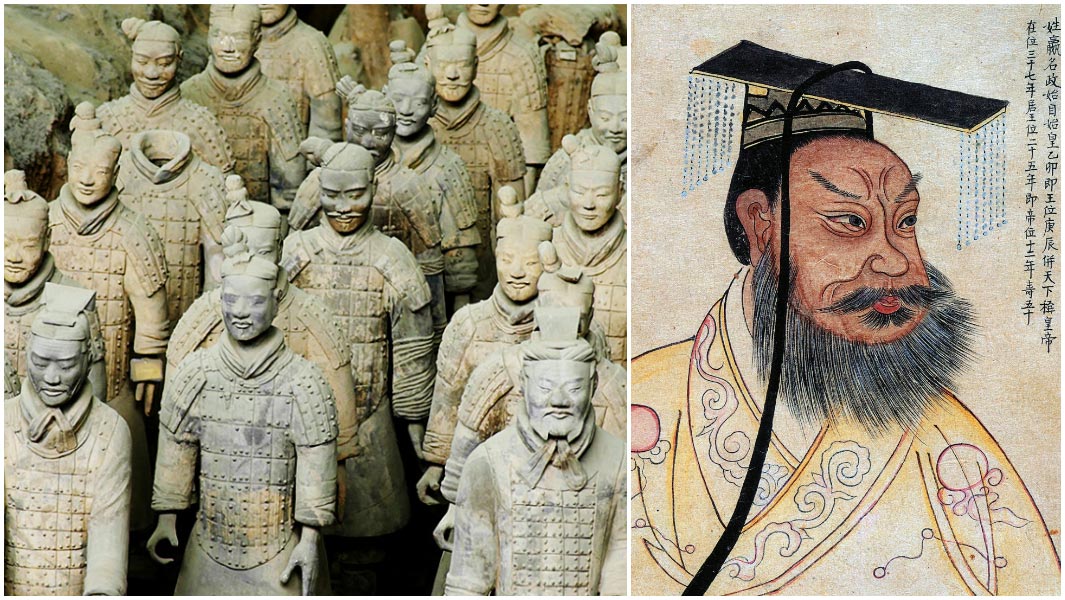

The Terracotta Army is often described as one of humanity’s greatest archaeological achievements, and rightly so.

More than 8,000 life-sized warriors, each with a unique face, hairstyle, and expression, stand in perfect military formation near Xi’an, China.

Discovered in 1974 by farmers digging a well, the army instantly reshaped our understanding of ancient China.

It revealed an emperor whose ambition knew no boundary—not even death.

That emperor was Qin Shi Huang, China’s first unifier, a man who conquered rival states, standardized writing and currency, and ruled with absolute authority.

But the Terracotta Army was never the end of his vision.

It was only the outermost layer.

Albert Lin, known for blending cutting-edge technology with archaeology, has repeatedly emphasized a chilling truth: the soldiers are just the surface.

What lies beneath them is the real story—and it is terrifying.

Lin has been granted rare access to restricted areas of the mausoleum complex, a privilege almost no one receives.

Standing near the sealed heart of the burial site, he described the experience as overwhelming.

This was not a museum.

This was not history at a safe distance.

This was a place still actively dangerous, still guarded by decisions made over 2,000 years ago.

The mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang is the largest burial complex ever constructed, spanning an estimated 22 square miles.

That alone is staggering.

But ancient texts and modern geophysical surveys suggest something even more unsettling: the complex was designed like an underground city, complete with defenses meant to last forever.

The Terracotta Army itself is arranged with ruthless precision.

Infantry in the front.

Cavalry positioned strategically.

Commanders overseeing the ranks.

This was not symbolic art.

It was military doctrine preserved in clay.

Each warrior was assembled using a blend of mass production and individual craftsmanship.

Legs were molded using coils of clay.

Torsos were formed in sections.

Heads were sculpted separately, ensuring no two faces were identical.

Once fired in massive kilns, the figures were painted in vibrant colors that vanished almost instantly when exposed to air after excavation.

They were never meant to see sunlight.

Alongside the warriors, archaeologists uncovered real bronze weapons—swords, spears, arrowheads, and crossbow bolts—many so well preserved they could still function.

Some were coated with chromium, an advanced technique that prevented rust for millennia.

This was not ceremonial.

It was preparation.

But Qin Shi Huang did not stop with soldiers.

The wider complex contains clay officials, acrobats, musicians, servants, animals, and ceremonial objects.

Entire courts were recreated underground.

Wooden chariots once stood where roads were laid.

Artificial waterways were constructed to mirror rivers above ground.

Ancient records describe palaces, towers, and infrastructure buried beneath the earth, all designed so the emperor could continue ruling in the afterlife.

Nearly 700,000 workers are believed to have labored on this project—mining clay, forging weapons, firing kilns, and shaping an empire below ground.

It was not a tomb.

It was a replacement world.

And then there is the inner chamber.

The central burial mound rises like a flattened pyramid, marking where Qin Shi Huang’s coffin is believed to rest.

It has never been opened.

Not because archaeologists lack curiosity—but because opening it could be lethal.

Albert Lin has repeatedly warned that the dangers described in ancient texts are not myths easily dismissed.

The historian Sima Qian, writing about a century after the emperor’s death, recorded that the tomb was protected by mechanical crossbows designed to fire automatically at intruders.

While no one has yet confirmed these devices directly, the concept is entirely plausible given Qin-era engineering.

But the greatest danger is not mechanical.

It is mercury.

Sima Qian wrote that rivers and seas of liquid mercury flowed through the tomb, crafted to imitate China’s great waterways like the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers.

In ancient China, mercury was believed to grant immortality.

Ironically, it is also deadly.

Qin Shi Huang himself likely died from ingesting mercury-based elixirs meant to prolong his life.

Modern science has delivered a chilling confirmation.

Soil samples taken around the mausoleum show abnormally high levels of mercury even today.

This suggests that mercury is not just legend—it is still there, slowly seeping through the earth after more than two millennia.

Mercury vapor is invisible, odorless, and lethal.

Disturbing the inner chamber could release toxic fumes capable of killing anyone inside.

This is one of the primary reasons Chinese authorities have refused to open the tomb.

The risk is not hypothetical.

It is measurable.

Some legends go even further.

Ancient accounts speak of sand traps designed to collapse like quicksand, rotating stone floors that flip intruders into hidden pits, and sealed chambers filled with flammable gases.

While these elements remain unconfirmed, they align disturbingly well with the emperor’s obsession with control, secrecy, and deterrence.

Albert Lin does not treat these stories lightly.

He argues that even if only a fraction of the defenses are real, the consequences of careless excavation could be irreversible.

Once mercury is released, it cannot be put back.

Once fragile structures collapse, they are lost forever.

That is why Lin advocates non-invasive exploration.

Using satellite imagery, ground-penetrating radar, muon detection, and remote sensing, Lin and other researchers are mapping what lies beneath without breaking seals.

The data suggests vast voids beneath the burial mound—spaces consistent with halls, chambers, and artificial waterways.

This is not a single coffin in a pit.

It is an underground metropolis.

And beneath the Terracotta Army itself, another unsettling detail emerges.

The warriors do not stand on bare soil.

They rest on carefully engineered foundations of rammed earth, compacted until nearly stone-hard.

Beneath that, some researchers believe mercury channels may extend outward from the central tomb, forming an additional defensive layer under the army itself.

In other words, the soldiers stand guard not only over the emperor—but over a hidden poison.

Imagine thousands of clay warriors unknowingly positioned above a slow-moving river of mercury, silent and unseen.

A final warning encoded into the earth itself.

Even now, after 2,000 years, the ground beneath the site may still be toxic.

Entering the wrong space, breaking the wrong seal, could mean death without drama or noise.

Albert Lin has described the mausoleum as one of the few places on Earth where archaeology and mortality intersect directly.

This is not just about preserving artifacts.

It is about respecting a system designed to endure forever.

The decision to leave the tomb sealed frustrates the public.

People want answers.

They want to see what lies inside.

But Lin insists that restraint is the most responsible form of exploration.

Once the inner chamber is opened, there is no undoing the damage—chemical, structural, or cultural.

Qin Shi Huang built this complex to send a message across eternity.

He was emperor in life, and he intended to remain emperor in death.

Every soldier, every weapon, every trap, and every drop of mercury reinforces that message.

More than two millennia later, it is still working.

The Terracotta Army stands above ground as a marvel of art and organization.

Beneath it lies something far darker—a reminder that some discoveries are not meant to be rushed, and some doors were sealed for a reason.

Albert Lin’s work has not exposed a treasure.

It has exposed a boundary.

And for now, that boundary remains unbroken.