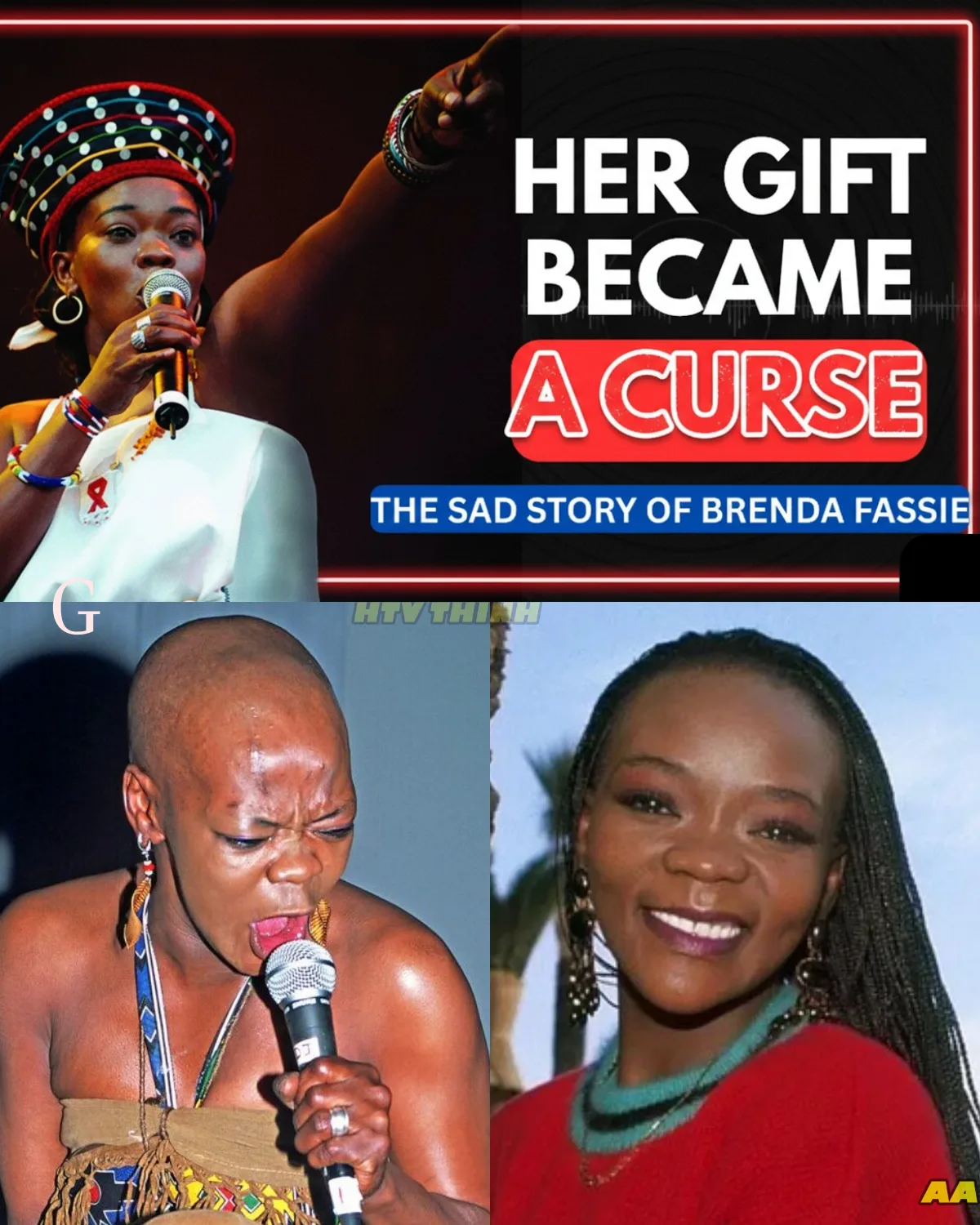

She Gave the World Her Voice — And Lost Her Own: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of Brenda Fassie

There are voices that arrive like weather—sudden, irresistible, and impossible to ignore. Brenda Fassie’s voice was one of those storms: born in a Cape Town township and carried like thunder across a continent. She was called the Madonna of Africa, a girl who turned broomsticks into microphones and grief into song. But if her voice built an empire of joy and defiance, the story that followed was the opposite of triumph: it was an unraveling, a human tragedy that read like a Greek drama with pop hooks and a chorus of regret.

This is the story of how Brenda gave the world everything she had — and in the end lost the thing that made her human: her voice, her dignity, and, tragically, her life.

The Langa Cradle: Where Music Became Destiny

Brenda’s story begins not with a recording contract but with a kitchen broom and a crate-turned-stage. Born in November 1964 in Langa, Cape Town, she grew up where music was not entertainment but breathing: church choirs, marabi guitars, tap-dancing fathers, and mothers who scrubbed houses by day to keep the family fed by night. Her father died when she was two; the absence left a hollow in a child that would later echo through her songs.

This is important: talent rarely appears in a vacuum. Brenda’s was forged in the furnace of necessity and ritual. Her mother’s Tiny Thoughts group was both refuge and apprenticeship. At ten, she performed not for fame but for food and the flicker of approval from a community that knew how to celebrate every small miracle. Langa taught her rhythm and taught her how to command attention even when the world wanted to look away.

Weekend Special: The Night a Girl Became a Nation’s Voice

At 14, a producer from Johannesburg heard Brenda and, in a line the transcript makes almost cinematic, said: “This is a voice of Africa.” But being heard is not the same as being free. Her mother hesitated — a child must finish school — and Brenda, restless, ran away to Soweto. That flight marked a girl who would not be brokered by fear.

Her breakthrough came with the Big Dudes and the timeless charge of Weekend Special — a song that felt like both a personal anthem and a continental declaration. It sold hundreds of thousands of copies, crossed borders, and made Brenda not just a pop star but a weather system over Southern Africa. Suddenly she was on TV, in Europe, the U.S., Brazil — a township girl transformed into the continent’s pop export.

And yet, within the glare of overnight success, something small but fatal began to shift: control left her hands. Managers, labels, and contracts took pieces of the life she thought she owned. The girl who had sung for survival found the industry hungry for margins, not magic.

Fame’s Pressure Cooker: The Cost of Being Unpolished Gold

Brenda’s rise was meteoric, but the industry is a refinery and not a school of care. She did not understand contracts; she only understood the sanctity of song. She was told what to wear, what to say, and when to smile. The script for her life came from executives who saw her as product rather than person.

This pressure coiled around her like a rope. She missed performances, walked off stage, disappeared after shows. To the press she became “difficult.” To a girl who had been a child first and a star second, the isolation felt like hunger. Her first marriage — public, lavish, and short-lived — imploded under the weight of celebrity. The man she married could not tolerate a fame larger than himself; domestic warfare replaced adulation.

From that wreckage came a private companion: cocaine. At first it was a lubricant for performance — energy before a show, relief after the lights dimmed. But substances do not remain tools; they become taskmasters. She started missing lyrics. She started falling asleep in dressing rooms. The press that had once adored her now called her the falling queen. The arc was familiar: adoration, appetite, addiction.

The Wreckage and the Rescue That Never Fully Came

By the early 1990s, Brenda’s life had become a cautionary headline. Friends drifted away, producers left, and her mother died in 1993—the twin griefs of loss and abandonment. In that vacuum she met a woman named Poyala. They were lovers and comrades in a moment of ruin, but together they fashioned a ménage of co-dependency: two souls consoling each other with the same poison.

One night Poyala overdosed. Brenda watched her die and did not call for help. That scene, as recounted in the transcript, is one of the most devastating moral images: the woman who sang about life holding the body of the woman she loved as life slipped away.

For a time, it looked like everything was over. A queen reduced to selling awards to feed herself. But the story is not only one of ruin. In 1998, the very thing many had declared finished roared back.

Mamesa: Resurrection in Three Minutes

Mamesa was less an album than a resurrection. Without a label, with only a producer and a battered will, Brenda returned to the studio. Mamesa — a Zulu word for a cry, a call for help — arrived like a prayer. It sold over 100,000 copies in a week and eventually hundreds of thousands more. The woman who had been sleeping on dirty floors produced a cultural reset.

What made Mamesa electric was its truth: the record sounded like recovery because it was stitched with the raw material of survival. Media returned, stadiums filled, and awards were re-gifted. For a moment, the story bent toward hope: the star wept and climbed, reclaimed her throne, and once more became the nation’s loudest anthem.

But the human heart does not reset like a radio dial. The addiction that had nearly consumed her remained a ghost in the dressing room. Comebacks that are not accompanied by sustained healing can be the cruelest of sirens: they reward the artist and then demand the same sacrificial vigilance she had not yet learned to give herself.

The Final Act: Collapse, Coma, and a Mother’s Day Funeral

In April 2004, after a show, Brenda collapsed. Brain damage followed. For two weeks she lay in a coma while a nation prayed and replayed her songs on loop. The public would not leave the gates; candles lined the streets. On 9 May 2004 — Mother’s Day — Brenda Fassie died. She was 39.

The list of proximate causes reads like a medical footnote: cocaine overdose, asthma complications, heart failure, brain damage. But the real cause is deeper: a constellation of industry exploitation, personal trauma, heartbreak, and a coping mechanism that became a coffin.

Her funeral was a national event. Ten thousand people attended her memorial; the city stopped and listened as Too Late for Mama — the song that had once announced her hard-won adulthood — now sounded like an elegy. That irony was cruel and perfect: the chorus that once signaled arrival now marked an ending.

The Psychological Backstory: A Voice that Sang to Silence Pain

We must look at Brenda not as a tabloid subject but as a human being with an interior geography of loss. Her father’s death at two, the grinding poverty of Langa, the sudden thrust into world stages — these are not background props; they are formative engines.

She never got to be a teenager. While others practiced the small experiments of youth, Brenda practiced performance as survival. When career demands replaced parenthood, addiction slid into the cracks. The psyche, deprived of childhood and nourished by applause, will often trade authenticity for any relief that does not require painful work. In Brenda’s case, cocaine offered speed and numbness; fame offered illusionary security; but neither could stitch the hole left by grief.

Her relationships show the same pattern: love, surrender, dependency, and loss. The woman who sang with joy was haunted by a private emptiness she tried to fill with performers, lovers, substances, and stages.

The Twist: The Comeback That Hid the Unresolved

If her life were merely a linear descent, the story would be a parable of inevitability. But Brenda’s last years introduce a tragic twist: the most spectacular comeback concealed an unresolved wound. Mamesa proved that talent and will can triumph over reputation — for a while. But the relapse shows that a comeback is not the same as deliverance.

That contrast is the sorrowful pivot of Brenda’s narrative: a phoenix that did not fully burn away the old ashes. The music industry can resurrect careers but it cannot always cure souls. The applause returned, contracts were signed, presidents were met — yet the core, the personal repair, was incomplete.

So the twist is not a revelation of guilt or scandal. It is the more unsettling realization that public recovery and private healing are not interchangeable. Brenda’s return to stardom was not the same as recovery; it was a stage of recovery that left her exposed to the old demons.

Legacy: A Nation’s Mirror, a Life’s Lesson

Brenda Fassie’s legacy is complicated because greatness often is. She gave South Africa a voice when the country needed to name itself. Her Black President was an anthem of hope in an era of struggle. Her songs — funny, fierce, tender — are still woven into the national memory. But she also became a cautionary tale about the appetite of fame and the vulnerabilities of artists who are thrust into marketplaces before they are emotionally equipped to handle them.

The lesson is not moralistic simplism. It is a human plea: care for artists as people, not only as commodities. Teach young talent the business of the world that will inevitably come for them. Prioritize healing as much as hit-making. And above all, recognize that genius is often brittle. The world can love a voice right into silence if it fails to love the voice’s owner.

Final Image: A Microphone in the Dust

Imagine the last frame: a broomstick turned mic on a dusty crate in Langa; then bright stadium lights; then one night, a dressing room lamp; then a hospital bed; then candles down a city street. Brenda’s life is a film of extremes, but the most enduring image is not of fame or tragedy alone — it’s of a young girl on a crate, singing to be heard. That child wanted to be seen and loved beyond her notes.

When the coffin slid into the ground and the country played Too Late for Mama, listeners realized the bitter truth the transcript offers plainly: sometimes we celebrate talent without remembering the person carrying it. We adored the voice, we did not always tend the life behind it.

Brenda Fassie’s story is a plea and a prophecy in one: celebrate art, but save the artist. Teach the young to read contracts, to seek therapy, to grieve, to build relationships outside of applause. Otherwise, the chorus of next time will read the same: a voice that gave the world everything — and someday, somewhere, lost her own.