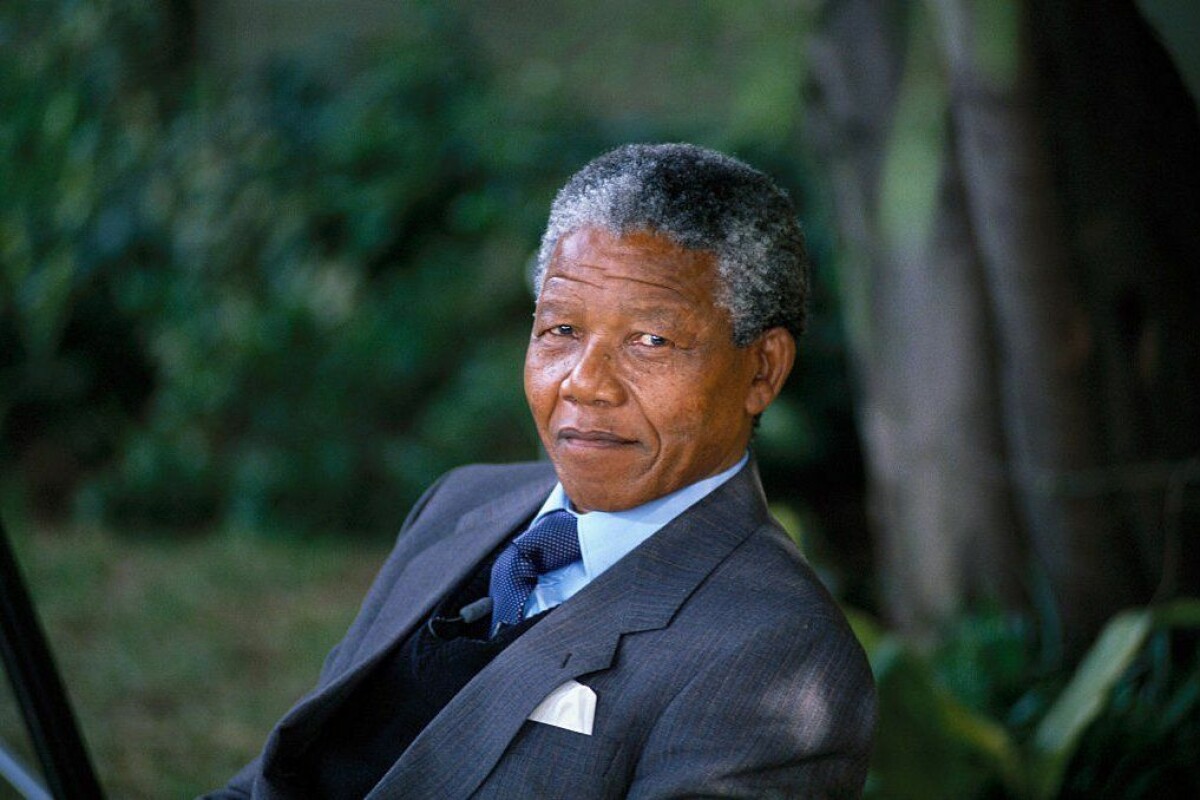

🚨 SHOCKING: Advocate Sikhakhane Unveils Nelson Mandela’s Deepest Secrets—The Truth About South Africa’s Downfall! 😱

The discourse begins with Sikhakhane’s stark observation that South Africa has been on a downward trajectory since Mandela’s presidency.

“We’ve been going down since Mandela,” he states, emphasizing the collective amnesia that seems to envelop the nation during moments of celebration.

Just as people may overlook the dangers of excessive revelry during New Year’s Eve, South Africans have failed to acknowledge the underlying issues that have persisted since the end of apartheid.

“We were caught up in euphoria,” he notes, a sentiment that resonates with many who witnessed the historic transition from oppression to democracy.

Sikhakhane’s critique extends beyond mere nostalgia; he argues that the compromises made during Mandela’s leadership were significant and detrimental.

“Even during Mandela, we were at the height of the biggest compromise about our people,” he asserts, suggesting that the celebrated leader was not immune to the systemic issues that plagued the nation.

While Mandela was revered for his role in dismantling apartheid, Sikhakhane argues that the love shown to him was often superficial, masking a deeper disdain for the black majority.

“White people loved Mandela but hated his race,” he declares, highlighting a paradox that many struggle to confront.

The advocate paints a picture of a society that has created a middle class, which serves as a buffer between the oppressors and the oppressed.

“Most of us…are that buffer that keeps hoping that things are fine,” he explains.

This middle class, while enjoying some level of comfort, is ultimately complicit in maintaining an oppressive system that continues to marginalize the majority.

“We own nothing except a vote and hope for nothing,” he laments, underscoring the disillusionment that pervades the lives of ordinary South Africans.

Sikhakhane argues that the political settlement reached in 1994 was fundamentally flawed.

He refers to it as a “problem” rather than a solution, asserting that the oppressive systems of the past simply evolved into more sophisticated forms of control.

“Apartheid is bad for capitalism,” he states, suggesting that the new regime offered minor concessions to placate the masses while preserving the status quo.

The metaphor of the “toilet spray syndrome” serves to illustrate this point—while the unpleasant realities of inequality remain, a superficial layer of cleanliness obscures the underlying issues.

As the conversation shifts to the judiciary and its role within this framework, Sikhakhane expresses concern over the philosophical underpinnings of the legal system.

“Judges and magistrates are hard at work,” he acknowledges, but questions the efficacy of their efforts within a fundamentally flawed system.

“When something is wrong philosophically, it doesn’t matter how hard we work,” he warns, drawing a parallel to a poisoned fountain.

No matter how diligently one might work to quench thirst, if the source is tainted, the outcome will remain detrimental.

The advocate’s critique extends to the political landscape, where he laments the lack of genuine alternatives.

“There’s no party in this country at the moment that would take over and things would change for our people,” he asserts, pointing to the pervasive influence of neoliberalism that has permeated South African politics.

This sentiment reflects a broader frustration with the political elite, who seem more concerned with maintaining power than addressing the root causes of inequality.

Sikhakhane urges for a re-examination of the narratives surrounding liberation and post-colonialism.

He highlights the need for public education that distinguishes between coloniality and colonialism, emphasizing the importance of confronting uncomfortable truths.

“We were a people like slaves,” he reflects, suggesting that the fear of confronting these realities continues to govern the nation’s psyche.

In conclusion, Advocate Sikhakhane’s revelations about Nelson Mandela and the state of South Africa challenge the prevailing narratives of triumph and progress.

His insights compel us to reconsider the compromises made during the transition to democracy and the ongoing struggles faced by the majority.

As the nation grapples with its past, Sikhakhane’s call for introspection and honest dialogue serves as a powerful reminder of the work that remains to be done.

If you found this discussion thought-provoking, please share your thoughts in the comments below and join the conversation about the future of South Africa and the legacy of its leaders.