‘I AM COMBAT READY’: The Police General Who Declared War on Cartels, Ministers, and a Captured State — And Risked Everything!

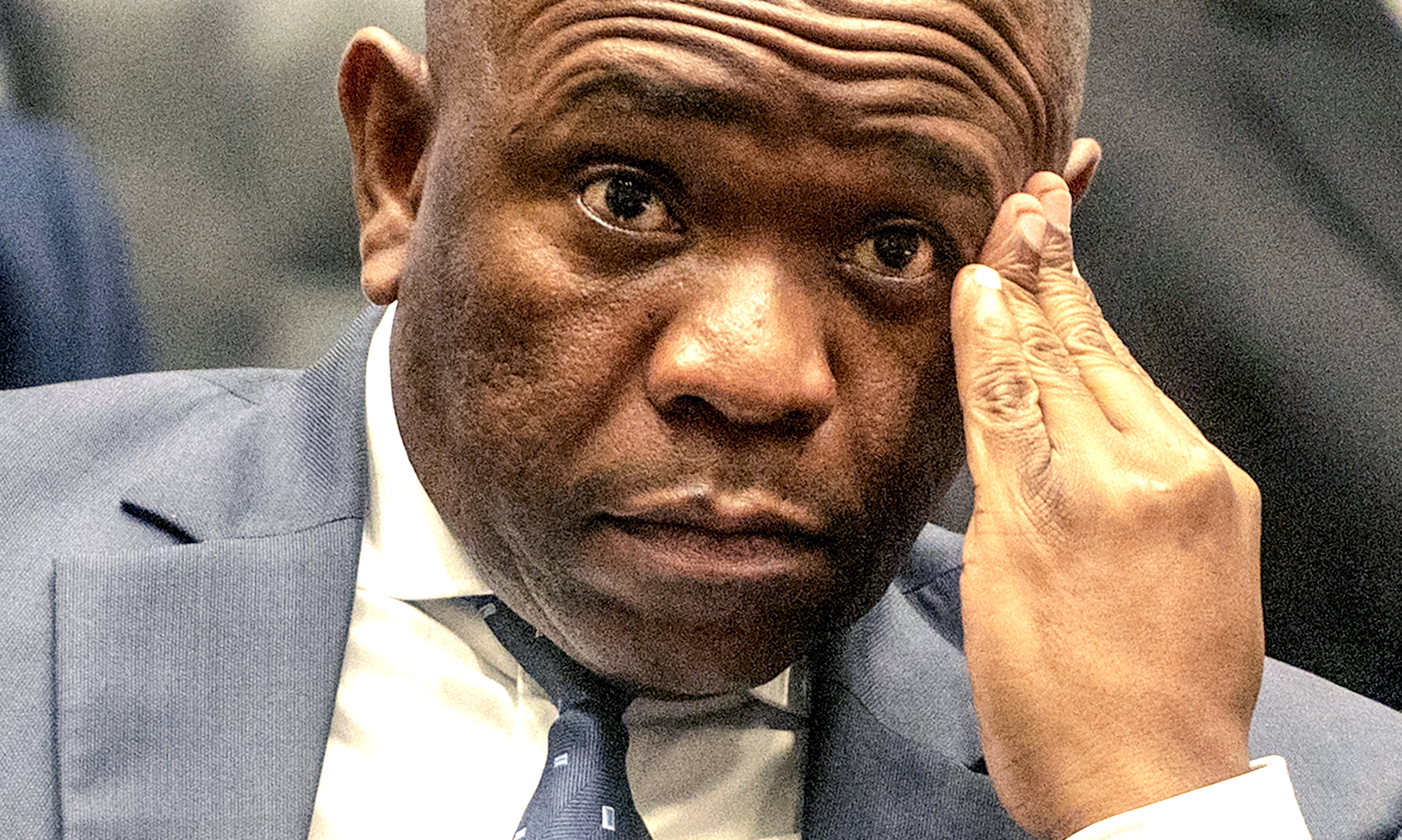

Cameras whir. Journalists lean forward. Armed officers line the walls like statues carved from tension. Then Lieutenant General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi, KwaZulu-Natal’s police commissioner, steps up to the podium in full tactical fatigues — not a suit, not a tie, but combat gear.

What follows is not a routine briefing.

It is a declaration of war.

“I am combat ready,” he says, eyes locked on the room.

“I will die for this badge. I will not back down.”

Gasps ripple through the press room. Within minutes, South Africa’s political world is on fire.

In that explosive hour-long address, Mkhwanazi does what no police general of his rank has ever dared to do so openly: he accuses powerful political figures of interfering in murder investigations and shielding criminal syndicates operating inside the state itself.

He names names.

He points fingers — including at the Minister of Police, Senzo Mchunu.

He speaks of political assassinations, stalled cases, vanished dockets, and cartels embedded deep within law enforcement.

This is not a rogue constable talking.

This is one of the most senior police officers in the country.

The nation is stunned. Supporters call him a hero. Critics call him reckless. And everyone asks the same question:

What kind of man risks his life, career, and family to say this out loud?

To understand Mkhwanazi’s defiance, you must go back — far back — to Edendale Township, outside Pietermaritzburg, in the late 1970s.

Born on 5 February 1973, young Nhlanhla grows up under apartheid’s brutal shadow. Gunshots echo at night. Homes burn on distant hills. Violence is not an exception — it is the atmosphere.

In March 1990, when he is just 17, the infamous Seven-Day War erupts in the valley. Nearly 200 people die. Thousands are displaced. Allegations swirl that apartheid-era police either stood by — or made things worse.

For the teenage Mkhwanazi, the lesson is seared into memory:

Law enforcement can either protect the innocent — or enable terror.

He chooses, early on, which side he wants to be on.

In 1993, as apartheid collapses, a 20-year-old Mkhwanazi raises his right hand and swears the police oath. South Africa is transforming, and so is its police service.

He joins Public Order Policing, walking straight into riots, political clashes, and pre-election chaos. Colleagues remember something unusual about him: restraint.

When stones fly, he doesn’t lose control.

When tempers flare, he pulls fellow officers back.

“We are law enforcement, not politicians,” he repeats.

In a force still shedding apartheid habits, he stands out.

By the late 1990s, Mkhwanazi is no longer just surviving — he’s excelling. He studies policing theory, earns qualifications, and gains a reputation for discipline and ethics.

Then comes the ultimate test: Special Task Force selection.

It breaks most who try.

Mkhwanazi doesn’t just survive — he dominates.

By 2005, he becomes one of the youngest commanders in STF history, leading high-risk hostage rescues, armed sieges, and counterterror operations. His philosophy is ruthless professionalism.

“No drama without evidence,” he tells his teams.

“A headline means nothing if the case collapses in court.”

That obsession with detail will later become his most dangerous weapon.

In 2011, everything changes.

With SAPS drowning in scandal, President Jacob Zuma appoints Mkhwanazi — just 38 years old — as Acting National Police Commissioner.

It should be the pinnacle of his career.

Instead, it becomes the beginning of exile.

Mkhwanazi audits secret police funds. He tightens controls. He follows the money. And then he does the unthinkable: he moves to suspend Crime Intelligence boss Richard Mdluli, a man facing serious allegations.

Behind closed doors, pressure mounts.

Back off, he’s told.

He refuses.

Weeks later, he is replaced. Then sidelined. Then effectively isolated.

Years later, he will testify:

“I believe I was punished for being disciplined.”

After his removal, Mkhwanazi is left without meaningful duties. He later claims he and other whistleblowers were monitored by state security, treated like enemies for refusing to play along.

He even warns Zuma personally about corruption at the top.

The response?

“Just give me time. I’m going to appoint someone else.”

The message is clear.

In 2018, political winds shift. Mkhwanazi is sent back home — this time as KwaZulu-Natal Police Commissioner, overseeing a province notorious for political assassinations.

He launches the Political Killings Task Team. Files are tracked obsessively. Evidence logged within hours. Witness protection tightened. Under his watch, hitmen are arrested, syndicates exposed, and links to business and police insiders uncovered.

But just as momentum builds, disaster strikes.

In late 2024, the Police Minister abruptly disbands the task team.

No warning.

No consultation.

And then comes the number that will haunt South Africa:

121 case dockets.

One hundred and twenty-one murder investigations removed from KZN and sent to Pretoria.

Mkhwanazi refuses to sign off. He says he does not trust what will happen to them.

He is right to worry.

By July 2025, with killings rising and files stuck in limbo, Mkhwanazi makes his choice.

Silence — or truth.

He chooses truth.

Standing before the nation, he alleges systematic political interference, protection of criminal kingpins, and sabotage of justice. Within days, the president suspends the police minister and announces a judicial commission of inquiry.

South Africa holds its breath.

At the Madlanga Commission, Mkhwanazi doesn’t shout. He doesn’t posture.

He produces spreadsheets. Courier logs. Audit trails.

Each of the 121 dockets, he says, represents a victim — and a stalled investigation. Some suspects, he claims, committed further murders while cases sat idle.

Then comes testimony from insiders alleging cartel money flowed into political and police structures. WhatsApp messages hint at leaked operations. Fixers. Middlemen. Silence bought with cash.

All allegations.

All fiercely denied.

But impossible to ignore.

Outside the hearings, protests erupt in his support. Civil society groups hail him as fearless. Critics accuse him of grandstanding and insubordination.

His security is tightened amid threats. His family remains exposed.

And still, he does not retreat.

“Fighting crime in South Africa,” he says, “means fighting criminals in the streets and criminals in our own ranks.”

As the commission continues and the nation waits for findings, one uncomfortable question lingers:

If a police general risks his life to expose a captured system — what happens when the spotlight fades?

Will South Africa protect leaders who refuse to bend?

Or will silence, once again, be safer than sacrifice?

In Edendale, a mural now watches over children walking to school. A police badge. Scales of justice. And beneath it, words attributed to the man who shook the system:

“Even if it costs me my life, let it be.”

South Africa must now decide whether that courage will be rewarded — or buried.