The Shocking Invasion That Led to the Downfall of Africa’s Most Notorious Dictator: How Idi Amin’s Arrogance Sparked His Own Destruction!

It was October 30th, 1978, a day that would forever alter the destinies of two nations.

In the early morning hours, under the orders of the infamous dictator Idi Amin, Ugandan tanks and soldiers thundered across the Kagera River, storming into northern Tanzania.

The air was thick with dust and arrogance as Amin believed this bold move would cement his image as Africa’s strongman.

To him, it was not just an invasion; it was theater, a performance designed to humiliate his longtime rival, Julius Nyerere, and prove that Uganda’s army was unstoppable.

But what Amin envisioned as a grand spectacle quickly spiraled into chaos.

His troops, known for their brutality and lack of discipline, looted villages, torched homes, and left behind a trail of destruction in Tanzanian territory.

Instead of instilling fear, the invasion ignited outrage.

Nyerere, a man known for his patience and diplomacy, suddenly had the perfect justification to strike back.

For years, he had sheltered Ugandan exiles longing to see Amin overthrown.

Now, with his homeland under attack, he had both the moral authority and the military resolve to act.

What Amin failed to grasp was that this gamble would unleash forces far beyond his control.

The invasion united Tanzanians like never before and forged a deadly alliance between Nyerere’s disciplined army and Amin’s exiled enemies.

What was meant to be Amin’s greatest display of power would become the very spark of his downfall.

In this article, we will explore the life of one of Africa’s most brutal dictators, how one single mistake led to his downfall, and the shocking consequences of his arrogance.

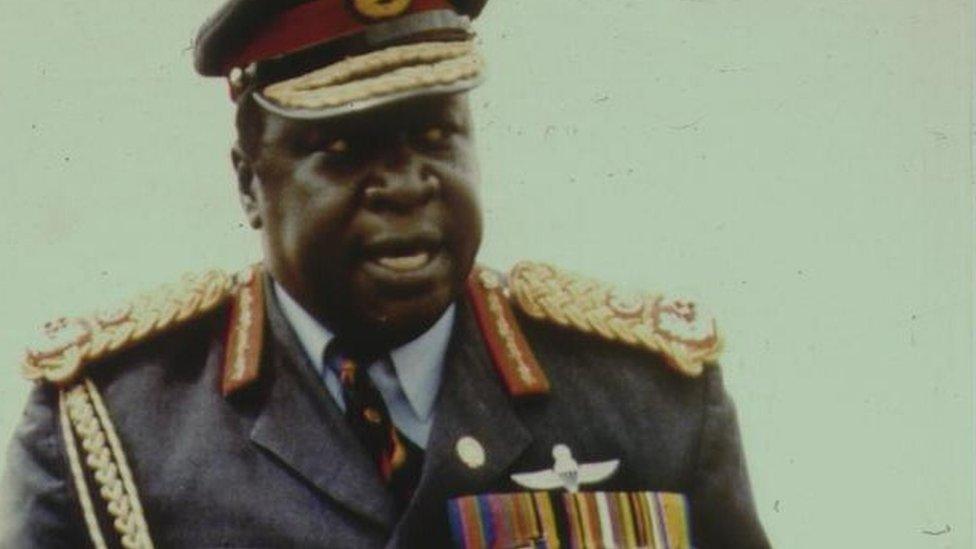

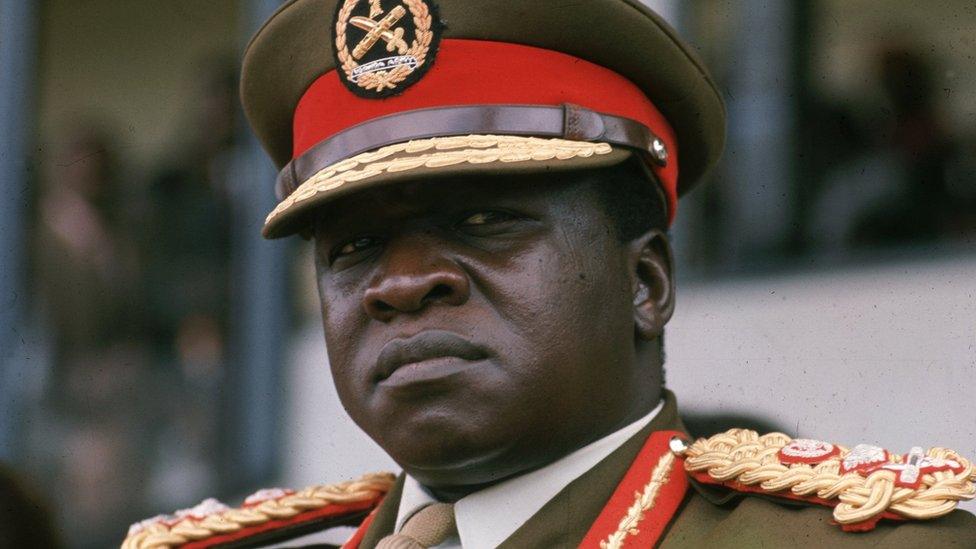

Idi Amin remains one of the most infamous figures in African and world history.

His story is a mix of mystery, brutality, charisma, and ambition—a tale of a man who rose from obscurity to seize power, only to plunge Uganda into one of the darkest chapters of its post-independence era.

To understand how Amin became the president of Uganda, we must trace his early life, military career, and the turbulent political climate that allowed him to rise.

Born on May 30, 1928, in Nakasero Hill, Kampala, Uganda, Idi Amin belonged to the Kakwa ethnic group, a small minority often overlooked in Uganda’s diverse ethnic landscape.

His father, Andreas Nyabira, was a farmer who later converted to Islam and changed his name to Aminada.

His mother, Aisha Ate, played an influential role in his early upbringing.

Amin had little formal education, reportedly attending school for only a few years, which left him functionally illiterate for much of his life.

However, what he lacked in education, he made up for with physical presence, strength, and adaptability.

Standing well over 6 feet tall with a commanding physique, Amin quickly stood out in his community and later in the army.

In 1946, he was recruited into the King’s African Rifles, a regiment of the British Colonial Army that drew soldiers from across East Africa.

This marked the beginning of his transformation from a poor boy in rural Uganda to a powerful figure.

Amin’s military career coincided with a period when Britain relied heavily on African troops to maintain colonial order and fight in distant conflicts.

He served in several military campaigns, including operations against Somali rebels in the 1940s and the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya during the 1950s.

His physical prowess and courage earned him promotions, even though his lack of education limited his ability to handle complex tasks.

By the early 1960s, he had risen to the rank of sergeant and later lieutenant, becoming one of the few Ugandans to achieve such a position in the colonial army.

Uganda gained independence from Britain in 1962 under the leadership of Prime Minister Milton Obote.

At independence, the Ugandan army was small and heavily influenced by the British.

Obote faced the challenge of maintaining control of the military while consolidating political power.

Amin, who had gained a reputation as loyal, physically intimidating, and willing to follow orders, became an ideal candidate for rapid promotion.

By 1965, he was one of the most senior officers in the Ugandan Army.

However, Amin’s rise was not without controversy.

During operations in eastern Uganda, he was accused of brutality and misappropriation of resources.

Still, Obote continued to shield him, partly because he needed a strong ally within the army.

The 1960s in Uganda were marked by growing ethnic and political tensions.

Obote, from the Lango ethnic group, faced opposition from Buganda, the most powerful kingdom in Uganda.

Relations worsened when Obote suspended the constitution and clashed with the Kabaka king of Buganda, Sir Edward Mutesa II.

Amin became Obote’s enforcer, leading an attack on the Kabaka’s palace in 1966 to crush Buganda’s resistance.

Amin’s loyalty to Obote was a façade; he was also ambitious.

He cultivated networks among soldiers, many of whom were from northern Uganda and Sudanese backgrounds like himself.

By the late 1960s, tensions began to grow between Obote and Amin.

Reports of Amin’s extravagant lifestyle, corruption, and involvement in smuggling raised questions about his loyalty.

Obote tried to curtail Amin’s power, but the army remained key to political power in Uganda, and Amin had positioned himself at its center.

The decisive moment came in January 1971.

Obote had traveled to Singapore to attend a Commonwealth heads of government meeting.

Sensing an opportunity, Amin and his allies moved swiftly.

On January 25th, 1971, Amin launched a military coup, seizing control of Kampala and key installations.

The coup caught Obote completely off guard.

Unable to return to Uganda, Amin declared himself president, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and head of government.

He justified his actions by accusing Obote of corruption and authoritarianism.

Initially, many Ugandans welcomed the coup.

Obote had become unpopular, and Amin presented himself as a man of the people—humble, approachable, and willing to listen.

Crowds cheered him in Kampala, and international recognition soon followed.

Britain and Israel quickly acknowledged his government.

Amin’s rise to power was sudden, dramatic, and, for many Ugandans, initially hopeful.

He promised to restore democracy, free political prisoners, and hand power back to the people.

However, beneath this charm offensive lay a ruthless determination to consolidate power.

Amin understood that his greatest threat came from the army.

He moved swiftly to eliminate Obote loyalists and rival officers, executing thousands of soldiers from Obote’s ethnic groups.

This ethnic purge extended beyond the military, targeting civil servants, intellectuals, and community leaders suspected of disloyalty.

By 1972, Amin had created a police state fueled by fear, with his secret police notorious for torture and extrajudicial killings.

Perhaps the most infamous act of Amin’s rule came in August 1972 when he ordered the expulsion of all Asians, mainly of Indian descent, who had lived in Uganda for generations.

Amin claimed that God had instructed him to rid Uganda of foreigners who were sabotaging the economy.

This act of nationalism proved disastrous, as the expelled Asians had been the backbone of Uganda’s economy.

Their departure triggered a massive economic collapse, plunging Uganda into poverty.

Amin crafted an image of himself as a larger-than-life figure, adopting grandiose titles and portraying himself as a pan-African hero.

His eccentric stunts and absurd proclamations fascinated and horrified the world.

At first, he enjoyed good relations with the West, but by 1972-73, relations soured.

He expelled Israeli advisers and aligned himself with Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi and the Soviet Union for support.

As time passed, Amin’s rule became a nightmare for ordinary Ugandans.

Arbitrary arrests, disappearances, and executions were routine.

The economy collapsed, leading to shortages of food and medicine.

Schools and hospitals deteriorated, and corruption flourished.

Amin sought to maintain a populist image, sponsoring public feasts and mingling with citizens at rallies, but the fear instilled in the population overshadowed any semblance of popularity.

By the mid-1970s, Uganda was a country in turmoil.

Amin’s regime had earned a reputation for mass killings and economic mismanagement.

Yet, he clung to power, relying on loyalty from the military and his ability to manipulate foreign relations.

However, his position was weakening.

Many Ugandans resented his rule, and thousands of exiles found refuge in neighboring Tanzania under President Julius Nyerere, who openly opposed Amin.

The rivalry between Amin and Nyerere was both personal and political.

Nyerere had supported Obote, and after the coup, he granted Obote asylum in Tanzania, where Ugandan exiles organized resistance.

Relations between the two countries grew tense, marked by border clashes and harsh rhetoric.

Amin viewed Tanzania as a threat to his survival, while Nyerere saw Amin as a tyrant who destabilized the region.

In October 1978, Ugandan troops mutinied against Amin near the Tanzanian border.

Instead of addressing the discontent within his army, Amin blamed Tanzania for supporting the rebels.

In response, he ordered a full-scale invasion of Tanzanian territory.

On October 30th, 1978, Ugandan troops crossed the Kagera River, believing they would rally national support.

However, this was a catastrophic miscalculation.

The Ugandan army was poorly disciplined and notorious for brutality.

Instead of consolidating their hold, the soldiers looted and killed civilians, further enraging Tanzanians.

The invasion gave Nyerere both the moral justification and domestic support to launch a counter-offensive.

Mobilizing the Tanzania People’s Defense Force (TPDF) and calling on Ugandan exiles to join the fight, Nyerere responded decisively.

By late November 1978, Tanzania had pushed Ugandan forces out of the Kagera region.

But Nyerere did not stop there; he declared that Amin’s aggression had to be punished permanently.

With the support of Ugandan rebels, Tanzania launched a full-scale invasion of Uganda.

As Tanzanian forces advanced, the weakness of Amin’s army became clear.

Years of purges and corruption had hollowed out the Ugandan military.

While Tanzanian troops advanced with strategy and coordination, Ugandan forces often fled or surrendered.

The myth of Amin’s invincibility crumbled.

By early 1979, Tanzanian and Ugandan exile forces captured key towns and closed in on Kampala.

Amin tried to rally support through bombastic speeches and appeals to foreign allies, but these efforts could not stop the inevitable.

On April 11th, 1979, Tanzanian and Ugandan rebel forces captured Kampala.

Amin fled the capital in disguise, abandoning his government.

Within days, his regime had collapsed, and a new transitional government was formed under Yusufu Lule, supported by Nyerere and the Tanzanian army.

After fleeing Uganda, Amin first went to Libya, where Gaddafi offered him refuge, and later settled in Saudi Arabia, living quietly under the protection of the Saudi royal family until his death in 2003.

Amin’s invasion of Tanzania was disastrous for several reasons.

First, he misjudged Tanzania’s resolve and underestimated Nyerere’s willingness to fight back.

Second, the invasion exposed the military weakness of Amin’s army, revealing it to be corrupt and incapable of sustained combat.

Third, it united Amin’s enemies, providing them with a common cause and powerful backing.

Fourth, the invasion destroyed any remaining international goodwill towards Amin, alienating even his previous allies.

Lastly, it triggered regime change, giving his enemies the perfect excuse to invade Uganda and remove him from power.

The fall of Amin’s regime marked a turning point in East African history.

Uganda entered a long period of instability as different factions vied for power in the years following his ouster.

For Amin, the invasion was the ultimate undoing of his power.

He had survived purges, economic collapse, and mass killings, but this reckless act of aggression destroyed his regime in less than six months.

Idi Amin’s decision to invade Tanzania in October 1978 was the single greatest blunder of his rule.

Born out of arrogance and a misreading of his own strength, this invasion ultimately exposed his weaknesses, united his enemies, and opened the door to his downfall.

By April 1979, his rule was over, his army defeated, and his once terrifying grip on Uganda shattered.

Amin’s downfall serves as a stark lesson in how reckless ambition and military miscalculations can end even the most brutal of dictatorships.

Idi Amin died in exile in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, on August 16th, 2003, at the age of 78.

After being overthrown, he lived quietly under Saudi protection, sustained by a government stipend.

In his final years, Amin suffered from severe hypertension, kidney failure, and other health complications.

His family requested he be allowed to return to Uganda for treatment, but the government refused, fearing unrest.

He slipped into a coma and died in King Faisal Specialist Hospital, buried quietly in Jeddah, far from the country he once ruled.