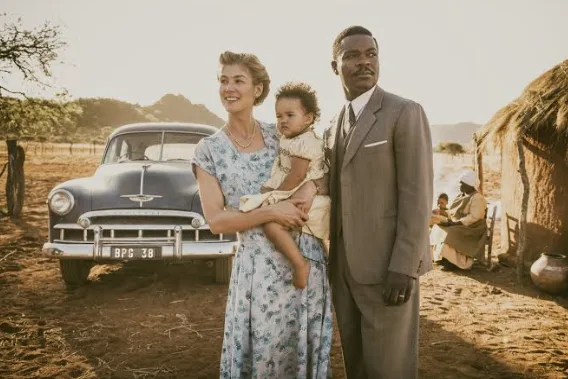

The Scandalous Love Affair That Shook an Empire: How an African Prince and a White Woman Defied Racial Norms!

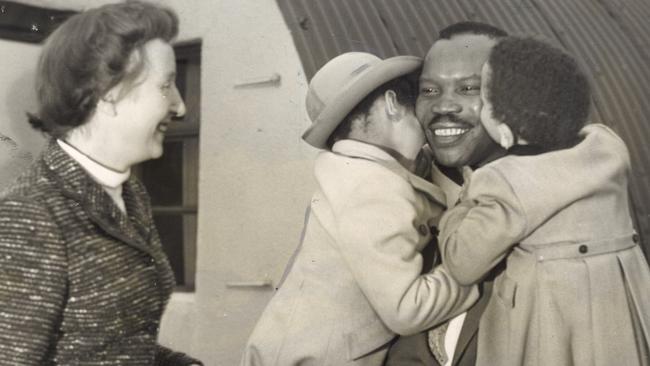

On the morning of September 29th, 1948, a love story unfolded that would send shockwaves across the globe and challenge the very foundations of colonial power! Seretse Khama, a dashing African royal heir, and Ruth Williams, a spirited white Englishwoman, dared to defy societal norms by getting married in a time when interracial unions were considered an absolute taboo.

This was not just a romance; it was a bold act of rebellion that would change the course of history!

Picture this: the world was still grappling with rigid racial hierarchies, and apartheid laws were just being introduced in South Africa, making it illegal for people of different races to marry.

Yet, in the heart of London, two people from vastly different backgrounds found love in a social gathering orchestrated by the London Missionary Society.

Their connection was immediate, but the stakes were incredibly high.

Seretse Khama was the heir to the Bamangwato chieftaincy in Bechuanaland (now Botswana), and marrying a white woman was seen as a direct challenge to the colonial order.

British authorities were in a frenzy, fearing that a white woman could become queen of an African tribe.

What would the white settlers say? How would this affect their control over the region? The marriage was not just personal; it was political!

Seretse was born on July 1st, 1921, into one of the most powerful royal families in southern Africa.

He was the grandson of Khama III, a legendary leader who had successfully resisted incorporation into white-ruled Rhodesia and South Africa.

From a young age, Seretse was groomed for leadership, but his path took an unexpected turn when he fell in love with Ruth.

Ruth Williams, a young Englishwoman from a modest background, was working as a clerk at Lloyds of London.

Their meeting was unplanned, occurring at a social event where mutual friends introduced them.

As they began to spend time together, their bond deepened.

Seretse was intelligent and reflective, while Ruth was warm and unpretentious.

They found solace in each other amidst the societal pressures surrounding them.

However, their love was not without challenges.

When Seretse revealed his intentions to marry Ruth, he faced immediate backlash from his family and advisors.

His uncle, Chief Khama, who served as regent of the Bamangwato, vehemently opposed the union.

He believed that such a marriage would undermine Seretse’s legitimacy as chief and provoke unrest among the people.

The British colonial officials also viewed the situation through a political lens, worried about how white settlers—and more critically, apartheid-era South Africa—would react.

The marriage sparked fear among colonial authorities that a white woman could become queen of an African people, an idea that sent shivers down the spines of those who upheld the racial hierarchy.

Despite the mounting opposition, Seretse remained resolute.

He insisted that his right to choose a wife was fundamental and that his people should judge him by his leadership, not his marriage.

In September 1948, after months of uncertainty and pressure, Seretse and Ruth decided to proceed with their wedding.

On that fateful day, they were married in a quiet civil ceremony in London.

The simplicity of the event contrasted sharply with the storm it unleashed.

News of the marriage spread rapidly, igniting outrage far beyond Britain.

South Africa, which had just institutionalized apartheid, reacted with fury.

Its leaders warned Britain that recognizing or tolerating the marriage would destabilize the racial order in southern Africa.

Britain, heavily dependent on South Africa for economic and strategic reasons, panicked.

What should have been a private matter was elevated into a matter of state.

The British government convened inquiries, debated Seretse’s suitability to rule, and framed his marriage as a political problem rather than a personal choice.

Ruth, who had married out of love rather than ambition, found herself vilified in the press.

She was portrayed as reckless, manipulative, or naive, while racist undertones permeated public commentary.

Seretse, meanwhile, was scrutinized not as a husband but as a potential threat to colonial stability.

In 1950, after a controversial investigation that many saw as biased, the British government banished Seretse from Bechuanaland, effectively exiling him for marrying the woman he loved.

Ruth followed him into exile, enduring isolation, financial hardship, and constant hostility.

Yet, the marriage endured.

What began as a meeting between two ordinary people in postwar London became a defining episode in African and imperial history.

Seretse and Ruth’s union exposed the hypocrisy of colonial rule, challenged racial ideology, and reshaped Seretse’s destiny.

Stripped of traditional authority, he eventually turned to democratic politics, leading Botswana to independence and becoming its first prime minister and president.

Their marriage, once condemned as scandalous, came to be recognized as a quiet act of courage, proof that a deeply personal decision could confront and ultimately outlast the power of empire.

The marriage between Seretse Khama and Ruth Williams was controversial and scandalous because it struck at the heart of the racial, political, and colonial order of the mid-20th century.

What appeared to be a private union between two individuals became a global crisis because it challenged systems that depended on racial separation, imperial control, and political expediency.

The most immediate source of controversy was race.

In 1948, interracial marriage was deeply stigmatized across much of the world.

In southern Africa, racial hierarchy was not only social but institutional.

Seretse, a black African royal, marrying a white British woman, directly contradicted the ideological foundation of apartheid.

To white minority governments, the marriage was not merely offensive; it was a dangerous symbol that undermined the belief in racial superiority.

The scandal was intensified by Seretse Khama’s status.

He was not an ordinary man but the rightful heir to the Bamangwato chieftaincy in Bechuanaland.

His marriage raised fears among colonial officials that a white woman would become queen of an African people, something they believed would disrupt traditional authority and provoke unrest.

British administrators worried that African subjects might reject a white chief’s wife, while white settlers feared the symbolic collapse of racial boundaries.

A decisive factor was British geopolitical anxiety.

Britain depended heavily on South Africa for trade, minerals, and regional security.

South African leaders applied intense diplomatic pressure, warning that recognition of the marriage would damage relations and destabilize southern Africa.

Rather than defend Seretse’s personal freedom, Britain prioritized its strategic interests.

This led to a series of investigations and political maneuvers designed to remove Seretse from power without openly admitting racial bias.

The marriage also exposed colonial hypocrisy.

Britain publicly promoted Christian morality, democracy, and individual rights.

Yet it punished Seretse for exercising those very principles.

Parliamentary debates and newspaper coverage turned a man’s choice of wife into a matter of state.

Ruth Williams was vilified in the press, often portrayed through racist and sexist stereotypes, while Seretse was depicted as irresponsible for choosing love over political convenience.

Finally, the scandal lay in what the marriage represented—a challenge to the idea that empire could control African lives at the most personal level.

By refusing to abandon Ruth, Seretse Khama defied both colonial authority and racial ideology.

The resulting exile, banishment, and political fallout transformed their marriage into a symbol of resistance.

In essence, the union was scandalous not because it violated moral values, but because it threatened systems built on inequality, fear, and control, making love itself a political act.

The marriage of Seretse Khama and Ruth Williams had far-reaching consequences that extended beyond their personal lives, affecting colonial policy, racial politics, and the future of Botswana.

At its core, the union challenged entrenched racial norms and exposed the moral contradictions of British colonial rule.

By marrying a white English woman, Seretse directly confronted the racial hierarchies of southern Africa, particularly apartheid South Africa, which viewed the marriage as a threat to its ideological and political stability.

Britain, under pressure from Pretoria, initially exiled Seretse, highlighting how colonial governance often prioritized political convenience over justice and individual rights.

The personal consequences for the couple were profound.

Seretse was stripped of his chieftaincy and banned from returning to Bechuanaland, while Ruth followed him into exile, facing social ostracism and isolation.

Despite these hardships, their marriage endured, demonstrating resilience, loyalty, and courage.

This perseverance became a public symbol of resistance against racial prejudice and colonial interference, inspiring international attention and sympathy.

Politically, the marriage shaped Seretse’s trajectory and ultimately Botswana’s destiny.

His exile pushed him from traditional leadership toward modern democratic politics, where he championed equality, non-racialism, and the rule of law.

Upon his return, he renounced the chieftaincy to lead Botswana as its first prime minister, guiding the nation toward independence and stability.

Beyond Botswana, their story has enduring symbolic power.

It stands as an inspiration for couples who challenge social norms, for leaders who confront injustice, and for societies striving to reconcile tradition with modern values.

Their marriage, once considered scandalous, is now celebrated as a courageous act that reshaped political and social landscapes.

Finally, their family continued this legacy.

Their children, particularly Ian Khama, carried forward the values of public service, national development, and principled leadership through both personal and political impact.

Seretse and Ruth Khama’s legacy is a testament to the transformative power of love, integrity, and resilience, proving that individual choices can echo across generations and alter the course of history.

In conclusion, the love story of Seretse Khama and Ruth Williams is a powerful reminder that love can transcend barriers and challenge oppressive systems.

Their marriage not only reshaped their lives but also altered the political landscape of southern Africa, inspiring future generations to fight for equality and justice.

Their story is not just a tale of love; it is a revolutionary act that continues to resonate today.