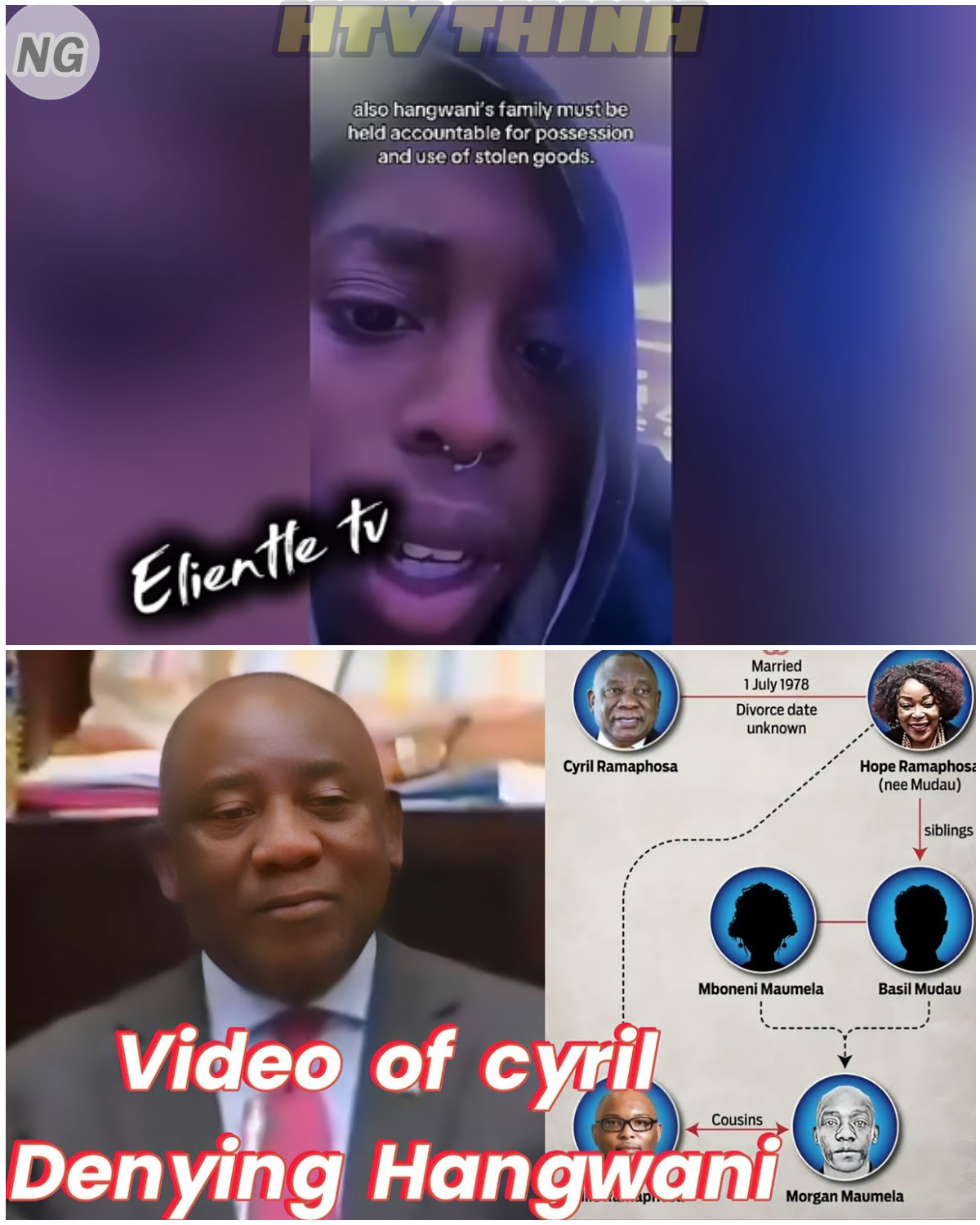

The moment captured on video, played and replayed across South African media platforms, is a chilling representation of the chasm between political power and public pain.

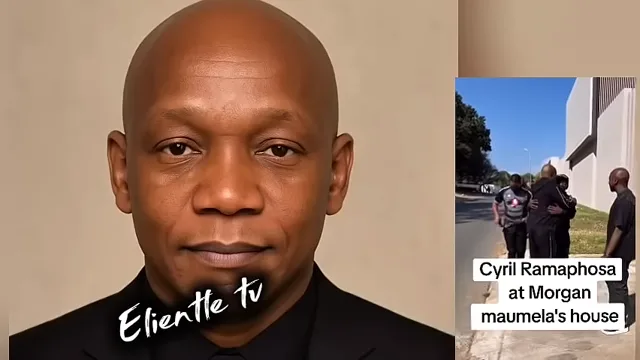

President Cyril Ramaphosa, standing before the nation’s legislative body, delivered a categorical and seemingly instinctive denial when confronted with questions about a highly controversial figure.

“No, you keep saying my nephew.

I don’t even know this gentleman.

And so let’s not even get there.

I don’t know.”

These short, sharp sentences were aimed at creating clear distance between the highest office in the land and Hangwani Maumela, the man whose name had, overnight, become synonymous with the grotesque theft of public funds intended for the sick and the dying.

The public reaction, however, was not one of relief or acceptance, but one of profound skepticism, fueled by the staggering details of the corruption Maumela is allegedly linked to.

This skepticism was only exacerbated by the subsequent official clarification from the Presidency, which awkwardly conceded a “historical family link” through a past marriage, contradicting the President’s absolute “I don’t even know this gentleman.”

The attempt to manage the optics of the crisis only managed to fuel the widespread belief that the political elite operates within a highly guarded ecosystem of mutual protection.

The fact is, many South Africans had no idea who Hangwani Maumela was until his name surfaced in connection with the R2 billion Tembisa Hospital tender fraud scandal.

“Guys, we didn’t know about this guy.

We didn’t know up until he was mentioned.

This guy lived his private life.

He was very private.”

Maumela, by all accounts, was an operator who preferred the shadows to the spotlight.

He reportedly maintained a minimal, if not entirely absent, social media presence.

Information about him on the internet is scarce, often posted by others attempting to piece together the fragments of a secretive life built on alleged graft.

This calculated anonymity is indicative of the type of high-level, organized financial crime that preys on state resources: operations conducted by individuals who seek to maximize profit while minimizing public exposure and accountability.

The myth of his privacy was shattered by the raid conducted by the Special Investigating Unit (SIU).

The SIU’s operation targeted Maumela’s lavish Sandton property, and what they found was immediately broadcast, generating a tidal wave of revulsion across the country.

“Look at the things that this guy owned.

Look at the cars that were taken there.

The cars that were seized there that were loaded in the truck.”

The sight of three high-end Lamborghini sports cars being loaded onto a recovery vehicle became the defining image of the Tembisa scandal.

This image did more to ignite public rage than perhaps any financial spreadsheet could.

“This image right here filled me with such rage and honestly just disgust.”

The public’s anger is not rooted in an issue with wealth itself.

“Now I have no issue with anyone who has made it in life and they have been able to acquire a good amount of wealth for themselves.”

The fury is specific.

It stems from the knowledge of where this money came from and what its absence means for the most vulnerable in society.

“But these three Lamborghinis here, this is a…

When I see this, I picture all the people at that hospital who have lost their lives, who have had to give birth on floors, who didn’t receive the medical attention that they needed because some [person] was busy stealing enough money to get these three Lambos.”

The sheer audacity of the alleged theft, directly from a health budget meant for basic medical care, is what makes the crime so heinous and the luxury so obscene.

It is a visible, tangible link between the opulent lifestyles of the connected few and the deadly deprivation faced by the poor.

This financial scandal is not abstract; it is a crime against humanity, measured in human lives and suffering at the Tembisa Hospital.

This is the hospital system that the late whistleblower, Babita Deokaran, paid the ultimate price to expose.

Deokaran, a high-ranking official in the Gauteng Department of Health, was gunned down outside her home in 2021 after flagging questionable payments, many of which were linked to the very tender irregularities that Maumela is now implicated in.

Her murder transformed the Tembisa tender fraud from a financial crime into a deadly political one, underscoring the lethal threat faced by those who dare to challenge the corruption network.

The seizure of the Lamborghinis, therefore, is not just a legal development; it is a moral outrage, illustrating the exact nature of the “greed that people talk about in the Bible.”

It represents the ultimate betrayal of the public trust, where healthcare—a fundamental right—is traded for supercars and Sandton mansions.

“And this probably isn’t even the tip of the iceberg.”

The speaker’s fear is that what has been exposed so far is only a fraction of the total looting that has taken place, suggesting the scale of the organized crime is far greater than current estimates.

“I am so, I’m trying so hard not to get worked up and emotional, but when you see things like this, knowing where this money came from, it should make everyone so incredibly angry.”

The call to action is clear: this anger must translate into a demand for justice.

“And I hope they make an example out of this person.

They need to.

They really, really do.

Knowing a function of a hospital and to steal enough funds to live like this.”

The justice sought must be proportional to the crime.

The sentiment is that every person who has received ill-treatment or any loved one who lost a person at Tembisa Hospital due to systemic failure “needs to have a few moments alone with this person,” expressing a raw, vengeful desire for direct accountability.

This is where the conversation turns to the uncomfortable and often undiscussed topic of family complicity.

The speaker raises a difficult, ethically complex question for the nation: Do we hold the families of criminal syndicates accountable?

The focus shifts from the primary perpetrator, Maumela, to his close relatives who lived in the ill-gotten luxury.

“His family members were sitting there and enjoying the money that comes from the graves of hundreds of poor people in Tembisa.”

The argument is based on the undeniable fact that these families were direct beneficiaries of the stolen funds.

They enjoyed the “100 million rand mansion,” the expensive trips, and the general luxury funded by money that should have saved lives.

“People who could have otherwise been saved and been providing for their families.

Who could have been alive breadwinners of their now orphaned children.”

The moral line is drawn sharply: those who benefit from the plunder of public funds, particularly funds tied to life-and-death services, cannot claim innocence.

The speaker makes a strong case for their complicity, stating that they are “the ones who may in fact have firsthand information of their crimes.”

Furthermore, their silence and inaction can be legally framed as obstruction of justice.

“Now, and on top of that, it’s something called obstruction of justice because they know this information.

They know it’s illegality, but they don’t report it.”

The call is for a legal and political framework that extends accountability beyond the central figure of the syndicate to those who are “complacent and they’re equally enjoying this money that is stolen from the blood of the poor and the downthrodden of this country.”

This demands a broader societal reckoning with the culture of silence that protects corruption.

The political significance of Ramaphosa’s initial denial in Parliament cannot be overstated.

It is viewed through the prism of his own ongoing corruption controversies, particularly the Phala Phala scandal.

When a President who promised a “New Dawn” of anti-corruption finds himself repeatedly having to deny intimate knowledge of, or association with, figures embroiled in massive financial scandals, his credibility evaporates.

The public’s cynicism is now at an all-time high, believing that the denial was less about truth and more about protecting the image of the Presidency and the ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC), ahead of a crucial election cycle.

The subsequent clarification that there was a “historical link” merely confirmed the fear that the denial was, at best, a half-truth designed to deceive.

It reinforces the pervasive belief that South Africa’s political elite is a tightly knit, protected circle, where lines of patronage and association run deep, often involving individuals with dubious financial dealings.

This case is not just about one man, one hospital, or one family.

It is about the systemic rot that has hollowed out the state and led to the tragic death of a brave woman, Babita Deokaran, who stood against it.

It is about a failure of governance so profound that basic healthcare is compromised for the sake of acquiring luxury European sports cars.

“This is where we are in this country.

Take a look at the image.

Let it sink in.

We’re not angry enough.”

The final, desperate plea is that the anger must be sustained.

It must be channeled into pressure for the full, uncompromising recovery of all stolen assets and the criminal prosecution of every individual involved, from the syndicate heads like Maumela to the public officials who enabled them, and perhaps, even their complacent families.

The image of the three Lamborghinis—paid for with the lives of the poor—must not be forgotten.

It must serve as a permanent, burning reminder of the price of silence and the urgency of the fight against corruption in Mzansi.

The denial in Parliament, the life of a whistleblower, and the three seized cars all tell a single story: the cost of political indifference is measured in blood and broken trust.

The country demands that the authorities not only investigate the crime but dismantle the entire syndicate, sending an unequivocal message that there is no safe haven for those who steal from the state, regardless of their political or family connections.

It is a test of the rule of law and the sincerity of President Ramaphosa’s anti-corruption rhetoric.

The nation waits, watching to see if justice will truly be done, or if the luxury cars will simply be replaced by new ones, bought with newly stolen money.

The energy and outrage evident in the public commentary must now be translated into an enduring political force capable of enforcing real, irreversible accountability across the board.

The stakes are too high, and the blood spilled is too real, to allow this story to simply fade away.

The Lamborghinis are loaded.

The political spotlight is on.

The question of who knew what, and when, and how far up the chain the complicity goes, remains the most critical question of all.

The fight for accountability is far from over.

The silence of those who benefited can no longer be tolerated.

The public’s anger must serve as the final, necessary catalyst for change.

The memory of Babita Deokaran demands nothing less than absolute justice.

The denial in Parliament has only intensified the spotlight on the connections that underpin the shadow economy of graft.

It is time for truth and full disclosure, regardless of the political cost.

The people of South Africa are watching closely.

They are counting the words, and they are counting the cars.

The time for simple denials has passed.

The time for comprehensive action is now.

The weight of the nation’s health and wealth rests on the outcome of this case.