A new and aggressive front in South Africa’s migration crisis has opened in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), where local community groups, often associated with the nationalist Operation Dudula movement, are taking the law into their own hands.

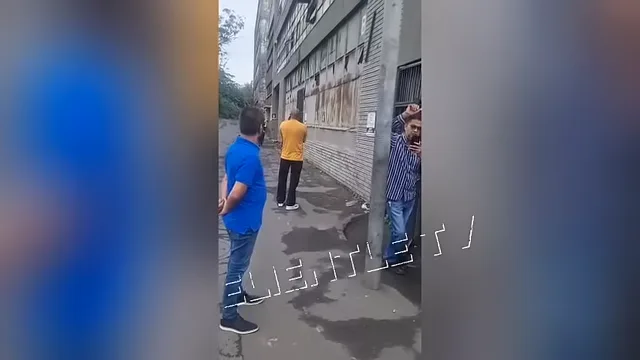

Dramatic video footage from the region recently captured Zulu women storming company premises, confronting foreign workers, and demanding their immediate removal.

The scenes are raw and uncompromising, punctuated by the activists’ relentless commands: “Go home. If you’re a foreigner, you can’t work today.”

The confrontational acts reflect the deep-seated frustration among South African citizens who feel their jobs are being unjustly seized, a belief that has metastasized into physical, on-the-ground enforcement.

One worker, identified as being from “Malawi,” was targeted and chased out, highlighting the specific focus on workers from neighboring African countries.

This direct action, however, exists in sharp contrast with the official, legalistic response coming from the highest echelons of government.

Addressing the crisis in Parliament, President Cyril Ramaphosa issued a stern warning, placing the legal and moral blame for the crisis squarely on the shoulders of businesses rather than the foreigners themselves.

The President emphasized that the Immigration Act strictly “prohibits anyone from employing illegal foreigners who are not documented.”

Under the law, the “employment of an illegal undocumented immigrant” is a severe offense, punishable by “imprisonment or a fine or both imprisonment or a fine.”

He stressed that while the Labor Relations Act “protect[s] foreign nationals who are certificated and documented,” employers who persistently hire undocumented individuals are “committing an offense.”

This practice, Ramaphosa argued, is often rooted in the pursuit of “cheap labor,” a form of corporate misconduct that unjustly deprives South Africans of employment opportunities.

He forcefully stated, “We are going to make sure that those employers stop what they are doing.”

To bolster enforcement, the President confirmed that the Department of Labor has presented an Employment Services Amendments Bill, which is designed to introduce employment quotas.

Furthermore, he was quick to defend the government’s stance against accusations of xenophobia, maintaining a strict legal distinction.

“We welcome and we’ve always welcomed workers from other countries who are certificated who are documented,” he said, drawing a parallel with global norms.

“South Africans even as they go to other countries they can’t just walk into a country and say I want a job without being documented or certificated.”

For Pretoria, the issue is not racial or national hatred, but adherence to documentation and the rule of law.

However, a deeper analysis of the crisis suggests that this domestic focus on employer compliance and undocumented status is an insufficient, even misleading, response to a continental catastrophe.

Commentators have seized on Ramaphosa’s remarks to launch a scathing critique of South Africa’s geopolitical timidity, arguing that the true root of the migration crisis lies far beyond the borders of KwaZulu-Natal.

The analyst observed that South Africa’s “progressive” constitution, its “freedom of speech,” and generous social services—including “social grants and… free health care”—make it an irresistible magnet for people fleeing oppression.

Yet, South Africa is failing in its expected role as the “big brother in Africa.”

The vast majority of the influx, the argument goes, are not economic opportunists but refugees escaping failed or dictatorial states where elections are brazenly rigged and citizens suffer immensely.

The commentator pointed to various nations, explicitly citing “what happened in Tanzania elections were rigged on daylight” and “what is happening in Cameroon,” alongside the perennial crisis in “Zimbabwe.”

The citizens of these countries are forced to seek “refugee,” “protection,” and a semblance of “political tolerance” in South Africa—the very rights and freedoms they are denied at home.

The cruel irony, the analyst stressed, is that when these victims of dictatorship arrive, “we then attack them.”

The failure is therefore laid at the door of the South African government, which refuses to “actually taking on head on on dictators in the in the continent that you can’t rig elections.”

This geopolitical inaction, according to the analysis, is the direct enabler of domestic xenophobic movements.

Groups like Operation Dudula, dismissively referred to as “this anarchist group… running a mock,” are not the cause of the problem, but a symptom of the government’s refusal to intervene where a dictator “doesn’t want to lose power at all cost.”

The commentator urged South Africa to step up and “lead by example,” to “assume that brotherhood and lead from the front,” much like the United States ensures stability in its own region.

Without a strong, interventionist foreign policy that protects African citizens from oppressive regimes, the inflow of refugees will continue unabated, no matter how many fines are levied on local employers.

The call is for President Ramaphosa to leverage the country’s “resources,” “the GDP,” and its historical leadership position to actively shape the African continent’s political direction.

The nation’s internal conflicts—from the women chasing foreigners out of companies to the government chasing employers—are ultimately mere distractions from the vast, unchecked political instability of the region.

Until Pretoria uses its power to create political stability across the continent, the migration crisis will persist, constantly threatening to tear apart the social fabric of South Africa and confirming the fears of those who believe the country is the victim of its own progressive ideals and its neighbor’s ruthless dictators.