The arrival of 153 Palestinians at OR Tambo International Airport, an event shrouded in a political fog so thick that President Cyril Ramaphosa himself deemed it “mysterious,” has detonated a national debate in South Africa that transcends humanitarian concern and strikes at the heart of the nation’s ethical contract, political sovereignty, and the dangerous phenomenon of public gaslighting.

The news that 153 individuals from Gaza, 23 of whom have since departed, landed seemingly without proper authorization, leaving 130 remaining in the country, immediately became a flashpoint.

While the government offered vague explanations, the humanitarian organization Gift of the Givers, through its founder Dr. Imtiaz Sooliman, quickly framed the context: these were people needing aid, fleeing a so-called genocide in Gaza, a situation demanding compassion and assistance.

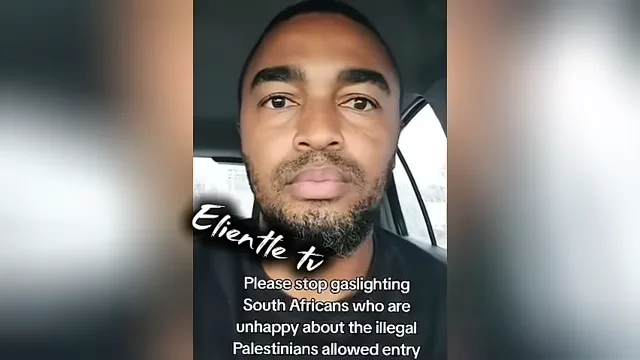

Yet, this humanitarian call was rapidly overshadowed by a furious counter-narrative, centered on the belief that South African citizens are being manipulated—or “gaslighted”—into accepting a political burden they never consented to bear, while their own national interests are compromised.

The crux of this counter-argument, articulated with raw force by commentators like Penwell, is not a rejection of the suffering in Gaza, but a profound rejection of selective, enforced political alignment.

The speaker makes a vital distinction: they are neither “pro Israel” nor “pro Palestine.”

Their alignment is strictly “pro innocent good people being killed,” whether those people are in Gaza, Ukraine, Russia, Sudan, Zimbabwe, or even the gang-ravaged Cape Flats.

This universal empathy, they argue, is a matter of heart, not allegiance to a distant political state.

This is the first layer of resistance against gaslighting: refusing to be boxed into a state-centric ideological conflict and insisting that human suffering is universally condemnable, regardless of geopolitical flag or affiliation.

The second, and perhaps most politically charged, layer involves deconstructing the historical relationship between the African National Congress (ANC) and Palestine.

It is an indisputable historical fact that the ANC, particularly under Nelson Mandela, forged a “healthy relationship” with Palestinian leaders, notably Yasser Arafat, promising mutual support and solidarity that was rooted in their shared anti-colonial and anti-apartheid struggles.

However, the speaker contends that this historical promise, an agreement between two sets of leaders, does not automatically translate into a compulsory obligation for every ordinary South African citizen.

They draw a personal analogy: if a person agrees to help a friend who helped them grow up, that obligation does not automatically transfer to their children, their friends, or their business associates.

It was a personal and political pact made by a political elite, not a referendum mandate from the South African populace.

Furthermore, this moral complexity is highlighted by pointing out the deep-seated financial and personal ties Mandela and even President Ramaphosa have cultivated with “many big Jewish business people in South Africa who have very close ties with Israel.”

The South African government’s foreign policy is thus presented as a web of contradictory elite relationships—one of historical solidarity with Palestine, another of contemporary financial linkage with Israel-aligned interests—none of which, it is argued, have anything to do with the “ordinary South African” who did not agree to bear the resulting burdens or choose a side.

This is where the political alienation becomes palpable.

The act of voting for a political party—be it the ANC, EFF, Action SA, or the DA—is primarily motivated by domestic concerns: the desperate need for service delivery, access to social grants, or simply a desire for less corruption and less looting of taxes.

It is “stupid,” the speaker asserts, to assume that a vote for the DA implies automatic solidarity with the United States, or a vote for the ANC mandates full financial and logistical support for Palestine.

Voters choose for local benefits, not global political alignment, and they should not be gaslighted into believing their vote constitutes a full ideological endorsement of every international cause championed by their chosen party.

The core of the “hypocrite” charge leveled at South Africans is also ruthlessly dissected and dismissed.

Social media commentators have been quick to accuse citizens who previously posted “Free Palestine” of being hypocrites now that they are reluctant to welcome undocumented arrivals.

The speaker counters this by drawing a clear, ethical line: you “can have empathy but it does not mean that you must be forced to agree to solutions that do not make sense.”

Solidarity for a distant people’s struggle is a moral position; forcing a geographically, economically, and structurally strained nation like South Africa to become the logistical solution is a different, and unsustainable, proposition.

The stark geographical reality is invoked: Palestine is “hella far,” incredibly distant from South Africa, yet its inhabitants landed with a suspicious ease that only confirms the belief that South Africa is “just very easy to get into,” a place where “you can land however you want” and “people will sort you out.”

This leads to the fiercest counter-challenge against the gaslighters: an accountability test.

To everyone online who is shaming South Africans, the speaker demands proof of their own tangible commitment.

“Show me the daily or the weekly or the monthly funds that you are giving to gift of the givers and the South African government to say, ‘Hey, please take care of those people. Here’s the money for their accommodation. Here’s the money for their food.'”

Furthermore, they challenge the online humanitarians to open their own doors: “Show us videos of you saying or showing us you taking them into your home. Let them come to your house and stay there. Feed them. Take care of them.”

The failure to make these personal sacrifices, while demanding financial and logistical sacrifice from the ordinary South African taxpayer, marks the gaslighters as the true hypocrites.

The speaker points to the staggering costs, such as the reported 120 million figure for the ICJ case—money taken from ordinary taxpayers to fight for causes that do not directly benefit the vast majority of citizens.

The argument is then buttressed by a historical comparison that refutes the notion that South Africa is simply repaying a debt of solidarity from the apartheid era.

While nations stood with South Africa during apartheid, exiles were never allowed to simply “take flights to any country and just land there willy-nilly.”

In places like Tanzania, Angola, and Lesotho, South Africans were “welcomed in,” but through structured, documented processes.

They were put in their “own camps,” they were “documented,” and their presence was known, controlled, and agreed upon by the host government.

The landing of the 153 Palestinians, therefore, is viewed not as an act of solidarity, but as a “crazy sovereignty violation.”

This leads to the damning, central accusation against the country’s leadership: President Ramaphosa, Ronald Lamola, and the ANC are “lying about not knowing how that plane got there.”

This alleged deception confirms a deeper, more dangerous reality: “South Africa is not a sovereign country anymore. It’s a free-for-all.”

This political impotence is directly linked to the country’s ruling elite, described as the ANC-DA coalition and its GNU partners, who are accused of serving only the interests of the wealthy—the Oppenheimers, Martin Mashall, Patrice Motsepe—and the business interests of foreign powers like China, India, Germany, and the US.

The provision of grants is cynical, merely to “shut up the poor” who are deemed “very dangerous,” but the real “donkeys” are the middle class who “break their backs to pay taxes” and whose concerns about the country’s ethical direction and diminishing sovereignty are disregarded.

The final ethical plea from the first commentator is for honesty in advocacy.

He calls upon those who champion foreign causes—whether they have family in Palestine, business interests in Ukraine, or simply align out of religious solidarity—to state their motives honestly.

They should say, “Look, those are my Muslim brothers and sisters. I stand with do that.”

But to “co-opt other people who are not Muslim, who have no links to Palestine, who don’t really care is wrong.”

This is coupled with a sharp accusation of selective compassion, asserting that many online activists who are “convenient online” about Gaza “don’t give a [__] about debts in townships” or the “killing of ordinary black and colored people in South Africa.”

The entire gaslighting phenomenon is thus exposed as a self-serving propaganda exercise, designed to achieve likes and be “seen as some humanitarian in the world,” but which is fundamentally “disrespectful to ordinary South Africans.”

The conflict, however, is not limited to immigration and political allegiances.

It spills into the cultural sphere, exemplified by the testimony of another speaker, Megan, a South African Jew and anti-Zionist, who provided a case study of institutional resistance.

She revealed an incident at a mental health conference in Cape Town where an Israeli mental health speaker pulled out.

The reason for the withdrawal was the speaker’s refusal to acknowledge and recognize the “genocide in Gaza.”

In an act described as “sneaky and so disgusting,” the conference organizers allegedly tried to “work around it” and “sneak her work back in” by having someone else present her presentation and slides.

This attempt at professional subterfuge, bypassing the political and moral position that led to the speaker’s absence, was deemed “unacceptable.”

Megan’s response, drawn from her experience at a pro-poor and anti-budget cuts gathering, was a demand for radical, institutional action: “All she had to do was say that she understood and recognized that there was a genocide in Gaza and she couldn’t do that.”

The remedy, she argues, is not piecemeal resistance but a “blanket boycott of anything Israeli and Israelis at anything anywhere in South Africa.”

This move demands that the pro-Palestinian movement move beyond individual, reactive calls to be “alerted to these moments” and instead achieve institutional sanctioning and banning of all Israeli institutions.

Finally, a third commentator reinforces the darkest political fear underlying the initial incident: the belief that the Palestinians’ arrival is “not the first patch batch of people coming to South Africa.”

This suspicion suggests that an unseen entity or individuals are “benefiting from these people coming to South Africa,” implying a clandestine operation or a racketeering enterprise exploiting the country’s porous borders and political weakness.

The shock that “there are Palestinians who who who came to South Africa whilst we did not know” underscores a terrifying sense of lost control, not just over the country’s borders, but over the government’s knowledge and transparency.

In sum, the mysterious landing of 153 Palestinians has served as a political catalyst, exposing a multi-layered crisis in South Africa.

It has forced a confrontation with the uncomfortable truth that historical solidarity cannot be weaponized to gaslight a tax-paying populace already struggling with domestic crises.

It has laid bare the alleged hypocrisy of a political elite seemingly more loyal to global finance and foreign interests than to the sovereignty and immediate needs of its own citizens, whom they are accused of disregarding as economic “donkeys.”

And it has shown how the global conflict has curdled into domestic ethical battles, demanding institutional sanctions and an unflinching honesty about the true motives—personal, religious, or political—behind all acts of advocacy.

The debate is ultimately about whether South Africa is a truly sovereign nation, capable of controlling its borders and setting a foreign policy that reflects the mandate of its people, or if it has become a “free-for-all,” controlled by an oligarchy and prone to the demands of political convenience, leaving its ordinary citizens to cry out for accountability and a return to ethical governance.