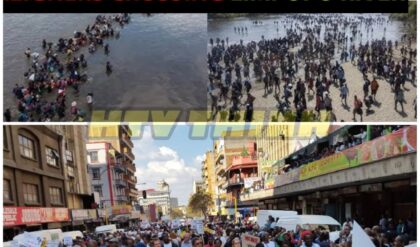

The heart of Johannesburg’s Central Business District (CBD) has become the latest battleground in an escalating conflict over urban order, economic survival, and national sovereignty.

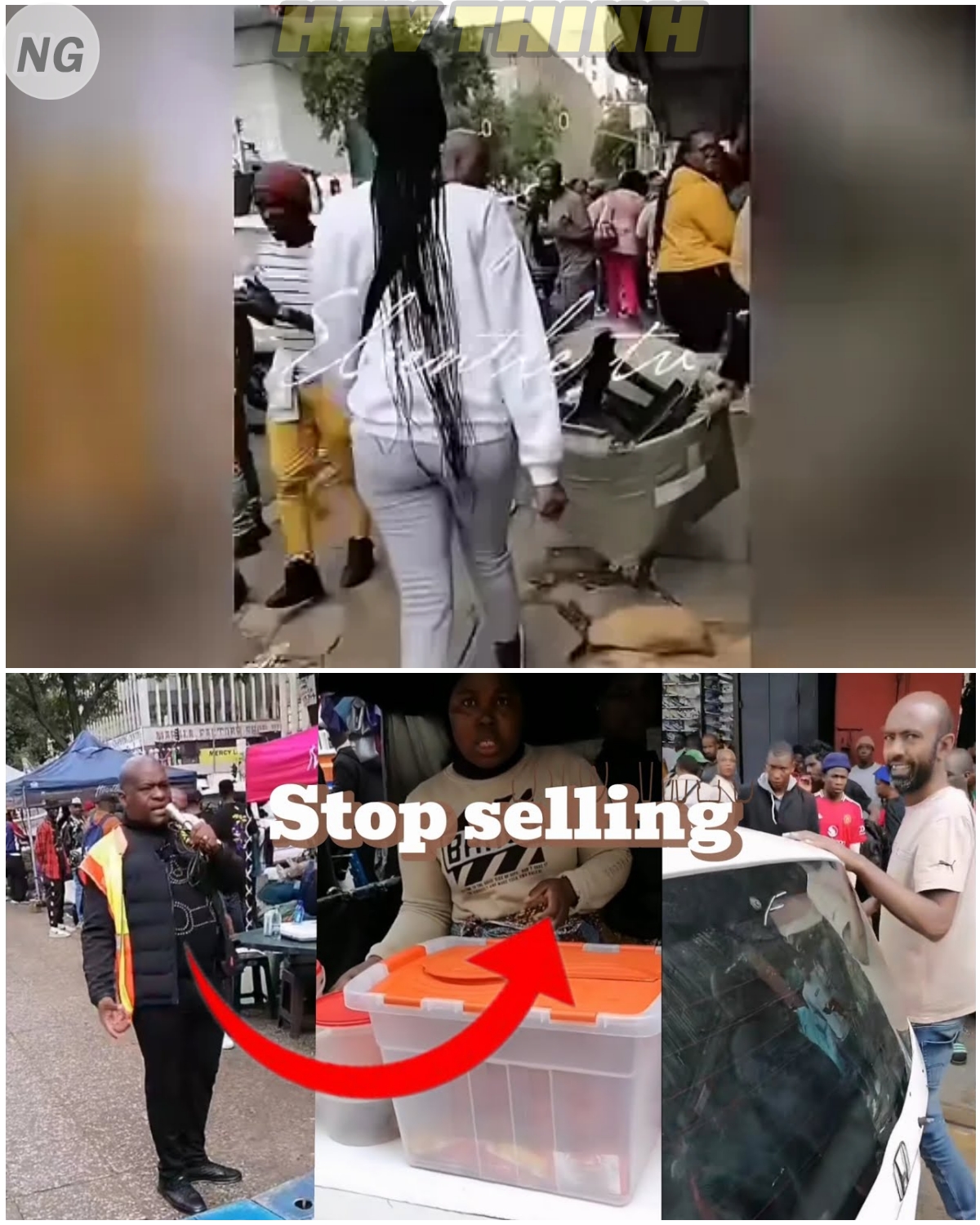

A recent high-profile enforcement operation targeting informal traders on key arteries like Small Street and Bree Street, led by a Member of the Mayoral Committee (MMC), has shone a harsh spotlight on the government’s struggle to manage its sprawling, vital, yet often anarchic informal economy.

The operation, documented in detail, is more than a clean-up; it is a declaration of the City’s intent to reassert control over public space, pushing an already volatile national debate on citizenship, migration, and the rule of law to a new breaking point.

Reclaiming the Pavements: Order vs. Chaos

The City of Johannesburg is operating under a mandate to enforce its Street Trading By-Laws, a legal framework designed to regulate the massive influx of informal traders who have, over years of economic hardship and insufficient regulation, completely overwhelmed public spaces.

The core of the official complaint, repeatedly voiced during the operation, is the total obstruction of the sidewalks and roadways.

The MMC’s frustration is palpable.

The streets, legally designated for pedestrian and vehicular traffic, have been transformed into densely packed, unregulated marketplaces where essential city functions are impossible.

The operation’s immediate goals are clinical and administrative: clearing the obstruction of public pathways, removing illegal structures and unpermitted goods (“Thatha lento, letha la izambel yokuthengisa le Thatha, asambeni”), and enforcing basic sanitation and hygiene standards.

Officials are seen directly confronting traders about the “insila” (filth/dirt), demanding that the area be cleared for refuse removal.

This enforcement drive is aimed at steering the informal sector towards compliance and formalization.

Officials repeatedly instruct traders to stop selling and instead go to the Home Affairs and regional offices to register, to obtain the necessary paperwork (“niyobhalisa ngendlela eytheni amaphepha Bani alokhethwa ngendlela e-right”).

The message is unequivocal: self-allocation of space (“Hhayi nizifake nina endaweni. Akwenziwa kanjalo.”) is illegal, and the only way to operate is through official channels.

The officials point out the lack of pedestrian access: “all the people can’t walk here… the lines [for designated stalls] are empty there.”

The Raw Reality of Resistance

For the thousands of individuals who rely on the CBD’s sidewalks for their daily income, the city’s operation is not about order; it is about outright survival.

The confrontation immediately escalates as traders, faced with the immediate seizure of their sole source of income, resort to defiance, arguing, and trying to hide their merchandise.

One trader’s desperate cry, “Qoqa xoqa mama valiwe shopwe,” captures the sense of loss and powerlessness.

The traders’ resistance is born from a profound sense of desperation and injustice.

They see the operation as a unilateral act of aggression by a government that offers them no viable economic alternative.

The emotional counter-argument—that their “shop” on the street is a necessary, self-made solution to the country’s high unemployment—is often dismissed by the authorities as a violation of the rule of law.

The informal sector views the city’s actions as arbitrary, often citing past court rulings that affirm their constitutional right to trade and challenging the city’s failure to provide adequate, designated trading space for the estimated over 25,000 informal traders in Johannesburg.

The Subtext of Sovereignty and Nationality

Beneath the visible conflict over space and hygiene lies a more corrosive national issue: the question of who has the right to access and profit from South Africa’s informal economy.

While the official language focuses on by-laws and compliance, the strong, pointed emphasis on “paperwork” and registration points directly to the underlying national tension regarding undocumented foreign nationals operating within the sector.

The push to ensure that “amaphepha Bani alokhethwa ngendlela e-right” (paperwork is sorted out the right way) is inextricably linked to the rising xenophobic sentiment and the political pressure exerted by movements like Operation Dudula.

This pressure is based on the popular, yet often legally challenged, assertion that informal trading should be reserved primarily for South African citizens.

While a recent High Court ruling confirmed that foreign nationals with valid permits or asylum-seeker status do qualify to trade, this does not alleviate the enforcement burden.

It merely shifts the focus: every trader, regardless of nationality, must now be able to produce the correct, legal permits—a challenge for many in this decentralized and rapidly expanding economy.

The enforcement in the CBD is therefore widely interpreted as a government move to appease domestic demands for border control and economic prioritization of citizens, using the technicality of by-law enforcement as the legal justification.

A City on the Edge

The scenes on Small and Bree Streets encapsulate the fundamental dichotomy facing the City of Johannesburg: the need for a “developmental approach” to nurture entrepreneurial opportunity, versus the necessity for “intensified by-law enforcement” to prevent complete urban collapse.

The MMC-led operation is a clear statement that the City is abandoning passive oversight in favour of proactive regulation.

However, this hard-line approach is highly volatile.

The removal of traders from the CBD without a clear, functional plan for their re-allocation and re-registration only deepens the cycle of poverty and chaos.

The traders simply move to the next corner, forcing the City into a continuous, resource-intensive cat-and-mouse game.

Ultimately, the battle for the pavements of Johannesburg is a microcosm of South Africa’s wider governance crisis.

It is a confrontation between the ideal of a well-ordered, rule-of-law-governed city and the harsh reality of an economy struggling to absorb millions of citizens and migrants, where the right to earn a living often overrides the obligation to follow the law.

Until the City can successfully marry enforcement with credible, large-scale formalization and allocation of space, the streets of the CBD will continue to be a deeply contested territory, perpetually on the verge of breakdown.