History does not always announce its deceptions with violence.

Sometimes it whispers them gently through beauty.

Sometimes it repeats them so often that doubt feels like betrayal.

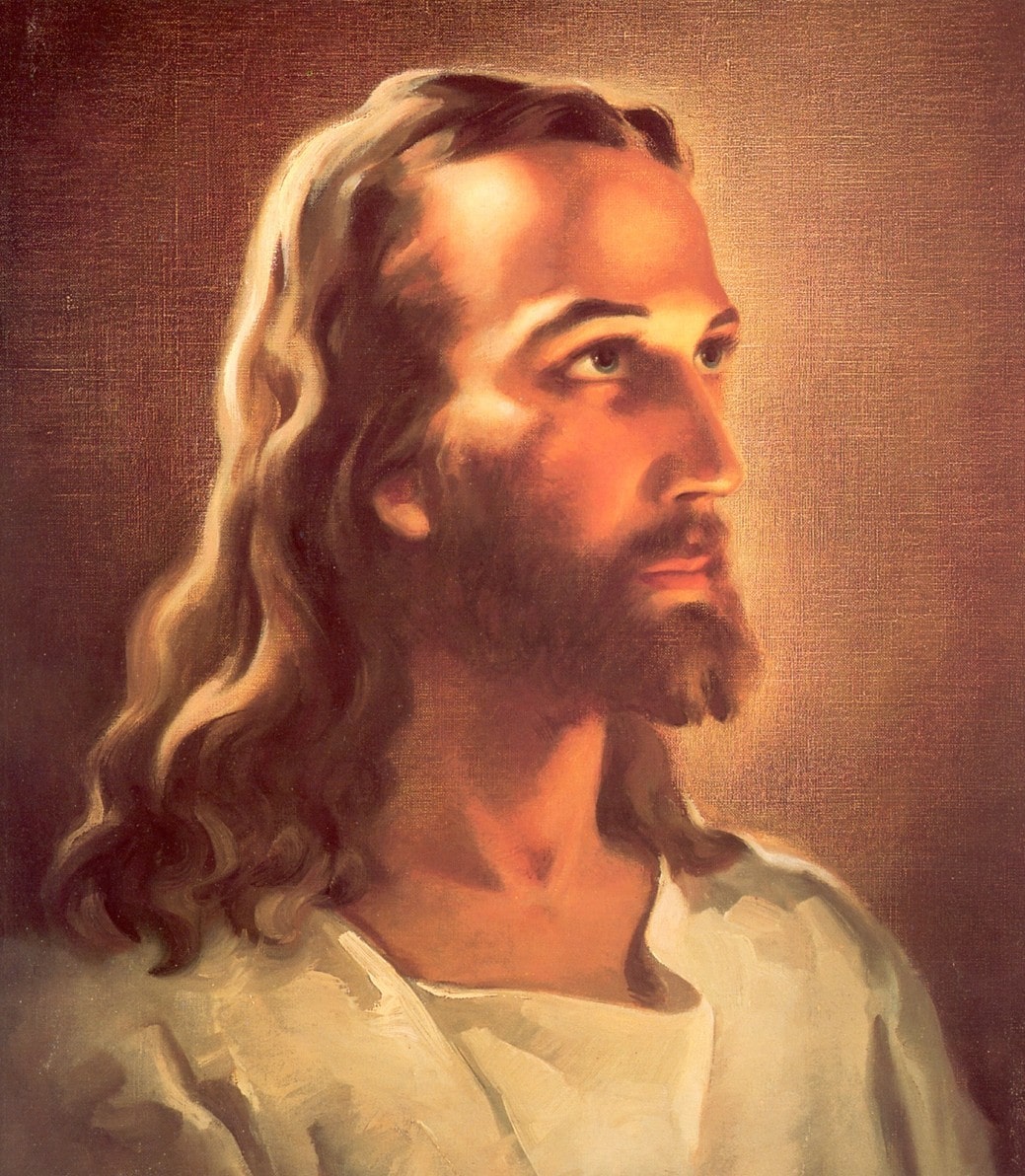

The image of Jesus Christ as the fair-skinned, light-eyed savior did not descend from heaven fully formed.

It emerged slowly, layer by layer, shaped not by eyewitness certainty but by centuries of longing, authority, and visual reinforcement.

When people see the same image long enough, it stops feeling like interpretation and begins to feel like memory.

And memory, once shared by millions, becomes nearly impossible to challenge.

The human mind is not a passive observer.

It fills gaps, harmonizes contradictions, and accepts repetition as truth.

Psychologists have long warned that mass perception can drift into collective illusion when reinforced by culture, authority, and emotional reward.

Religion, with its rituals, icons, and inherited imagery, is uniquely powerful in this regard.

And Christianity, more than perhaps any other belief system, became inseparable from the face it repeatedly showed the world.

Yet the earliest texts were strangely silent.

The Gospels describe miracles, suffering, rage, tenderness, blood, and resurrection—but almost nothing about the physical man himself.

No height.

No eye color.

No skin tone.

No defining feature to anchor the imagination.

That silence created a vacuum.

And vacuums never remain empty.

Into that void poured centuries of art, theology, and empire.

Jesus was painted not as he likely appeared—a Jewish man from first-century Galilee—but as cultures needed him to appear.

Familiar.

Reassuring.

Powerful.

And eventually, European.

The result was not a single image, but a psychological consensus so strong it blurred the line between faith and fact.

Then there is the letter.

Attributed to a Roman official named Aurelius Lentulus, the document claims to offer a direct physical description of Jesus Christ.

Lentulus, according to tradition, served in Judea during the reign of Emperor Tiberius and reported regularly to Rome.

Unlike poets or theologians, he was not writing for worship.

He was writing for administration.

Observation.

Control.

The tone of the letter is calm, precise, almost unsettling in its intimacy.

It does not preach.

It catalogs.

The Jesus described there is striking, composed, magnetic.

Fair hair, parted at the center.

Penetrating blue eyes.

A beard carefully shaped.

A face without blemish or excess emotion.

He inspires love and fear simultaneously.

He never laughs.

He sometimes weeps.

He commands without shouting.

It is a portrait that feels eerily familiar—almost too familiar.

It mirrors the Christ of Renaissance canvases, medieval icons, and modern devotional art with uncanny accuracy.

And that is precisely the problem.

If this letter truly came from the first century, it would be revolutionary.

It would anchor centuries of art in historical reality.

But if it did not—if it emerged later, shaped by the very imagery it appears to confirm—then it is not evidence.

It is echo.

A feedback loop where belief creates image, and image reinforces belief until origin becomes irrelevant.

Most modern scholars remain skeptical.

Linguistic analysis suggests medieval phrasing.

No contemporary Roman records reference such a report.

The title attributed to Lentulus does not align cleanly with known Roman offices of the time.

And yet, the letter persists, circulated endlessly online, cited in sermons, whispered as forbidden knowledge.

Its power lies not in proof—but in how desperately people want it to be true.

This hunger for a face reveals something profound.

Humans crave embodiment.

An invisible god is difficult to love.

A faceless savior is hard to follow.

So the mind supplies what the text withholds.

Over centuries, this shared imagination hardened into certainty.

The phenomenon extends beyond Lentulus.

Other supposed eyewitness descriptions—letters attributed to Pontius Pilate or Gamaliel—surface periodically, each offering confirmation, each shadowed by doubts.

They promise what scripture denies: visual closure.

They seduce believers with the illusion of proximity.

And illusion, when comforting, spreads easily.

Art accelerated the process.

Early Christian imagery borrowed heavily from Greco-Roman ideals.

Jesus appeared youthful, radiant, Apollo-like.

Divinity, in classical culture, meant beauty and symmetry.

Later, as Christianity institutionalized under Constantine, the image shifted.

The suffering redeemer emerged.

Bearded.

Mature.

Eternal.

Not youthful god, but cosmic judge.

The transformation was not accidental.

Power required gravitas.

Empire required authority.

Then came the legends of images not made by human hands—the acheiropoieta.

The Mandylion of Edessa.

The veil of Veronica.

The Holy Face miraculously transferred onto cloth.

These relics claimed divine origin, bypassing art entirely.

They were not interpretations; they were supposed imprints.

And once accepted, they became templates.

Artists no longer imagined Christ—they copied him.

By the Middle Ages, deviation became dangerous.

To paint Jesus differently was to risk heresy.

Uniformity replaced curiosity.

When the Renaissance arrived, artists like Antonello da Messina and Albrecht Dürer infused personal identity into Christ’s face, subtly merging self and savior.

Dürer’s 1500 self-portrait stares directly outward, symmetrical, frontal, unmistakably Christ-like.

It is devotion—and declaration.

The boundary between worship and self-image dissolves.

As European power expanded through trade, mission, and conquest, this face traveled with it.

It became global.

In Africa.

In Asia.

In the Americas.

Indigenous features were erased, replaced by imported sanctity.

A single image colonized belief.

Even attempts at scientific grounding did not escape controversy.

The Shroud of Turin, analyzed by researchers like Giovanni Judica-Cordiglia, offered measurements, proportions, even cranial capacity.

A tall man.

Striking symmetry.

Exceptional presence.

For some, it confirmed faith.

For others, it merely demonstrated how deeply the desire to see had penetrated even science.

Early theologians sensed the danger.

Augustine warned that everyone imagines Christ differently, and that no image should become idol.

Cyril of Jerusalem suggested Jesus appears differently to each soul—vine, door, lamb—never fixed, never possessed.

Their caution went largely unheeded.

Because a fixed face is comforting.

It ends uncertainty.

It turns mystery into merchandise.

So the question lingers, heavy and unresolved.

Did humanity collectively hallucinate a savior’s face? Not in madness—but in meaning.

Did repetition, art, authority, and longing converge into a shared vision mistaken for memory?

Perhaps the most unsettling truth is not that we got his face wrong—but that we needed a face at all.

Christianity ultimately teaches that seeing comes later.

That the true encounter transcends flesh, pigment, and cloth.

That whatever face awaits believers is beyond culture, beyond history, beyond illusion.

And yet, until that moment, humanity continues to stare at the same familiar image—searching not for accuracy, but for reassurance.

And maybe that is the most human revelation of all.