The recent tragic deaths of three South African police officers, Constables Sabia, Matt Lala, and Chinu, are not just another set of statistics in the ongoing battle between law enforcement and organized crime.

These were three officers who worked in the country’s crime intelligence division, specializing in cyber security, and whose deaths have sparked one of the most chilling investigations in South African policing history.

The officers were traveling from Bloom Fontaine to Limpopo, a journey that should have been routine.

However, their bodies were later discovered in Johannesburg under circumstances that defied explanation.

The route they were on made no sense, and the condition of the vehicle raised immediate suspicion.

The left side of the car was pristine, with no damage, yet the car had supposedly crashed through a barrier before plunging into water.

Investigators quickly realized that the official story didn’t add up.

The case took an even more bizarre turn when a civilian, who had been driving alongside the officers, came forward with a statement.

The witness had sensed something was wrong, prompting him to check who was in the officers’ vehicle.

After confirming the identities of the passengers, he drove on, but his discomfort raised questions that were never fully explored.

This line of inquiry was quickly dismissed, and the investigation, led by General CIA, seemed to be purposefully narrowing its focus on what seemed like an accident.

The lead investigator, General CIA, was specifically chosen to handle this case, and he had publically assured that this was a top priority for the SAPS.

However, the investigation quickly turned in an odd direction, leaving many wondering if it was being mishandled or even sabotaged.

The official reports about the investigation consistently failed to address crucial questions, and the families of the deceased officers were left with more doubts than answers.

To understand the full significance of this case, we need to grasp the context these three officers were operating in.

They weren’t just regular cops.

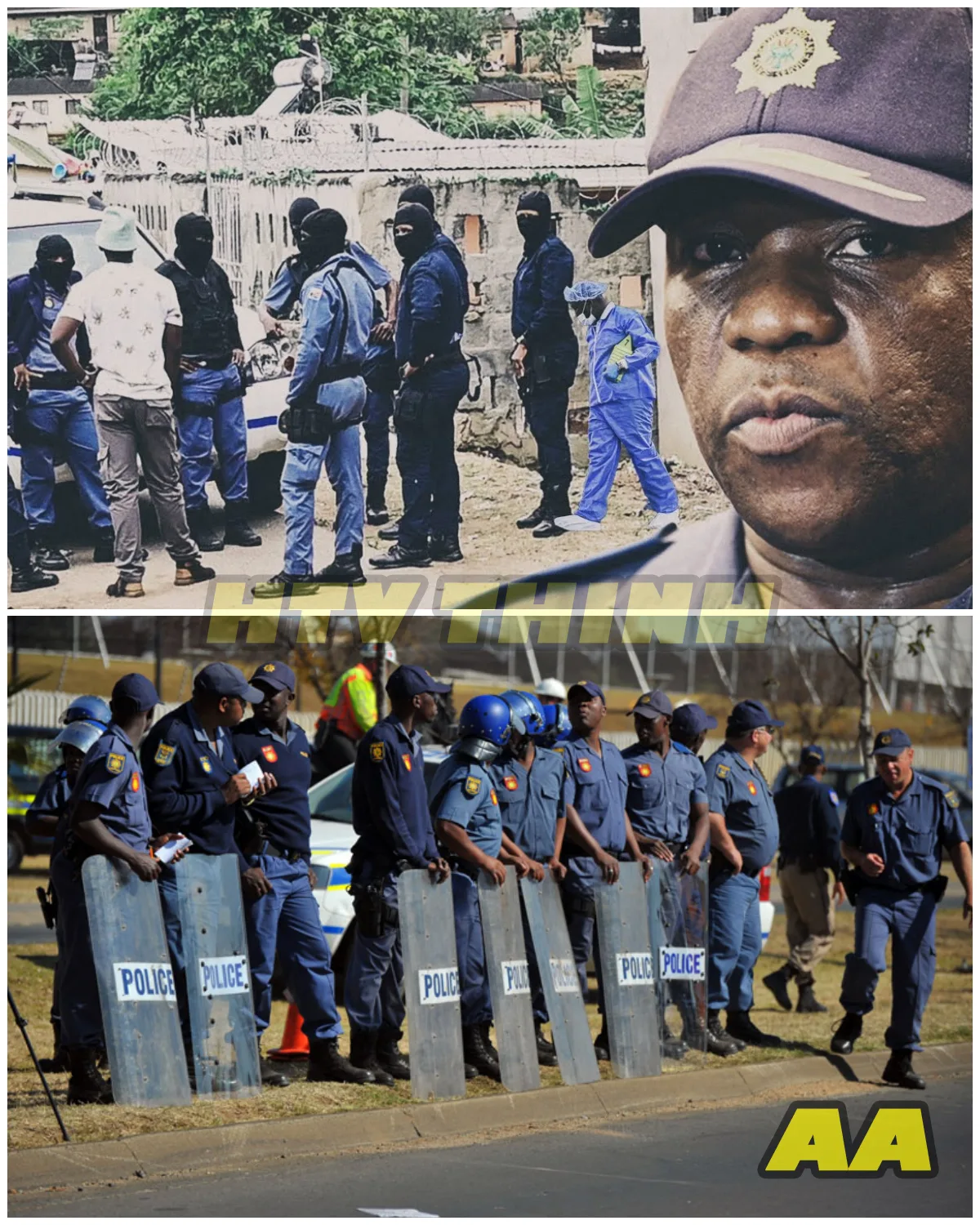

They were part of South Africa’s crucial crime intelligence division, which plays an integral role in gathering information, infiltrating criminal syndicates, and preventing crime before it happens.

This division is often the backbone of successful policing, with 80% of effective operations relying on intelligence work.

The systemic issue is simple: If you want to operate freely in South Africa’s criminal underworld, one of the first things you need to do is neutralize crime intelligence.

And this is precisely what has been happening.

Lieutenant General Sanson Kwanazi, a key figure in the investigation, has been publicly raising alarms about how crime intelligence is being systematically dismantled by political interference and bureaucratic paralysis.

On December 31st, the Minister of Police issued an astonishing directive that froze crime intelligence positions in KwaZulu-Natal.

No new hires were allowed, and existing positions remained vacant.

This, at a time when the country’s crime intelligence system needed reinforcements.

General Kwanazi, who had voiced concerns about this decision, argued that it left South Africa vulnerable, particularly in the fight against organized crime.

But the situation is even more dire when we look at how officers involved in key operations were being removed or sidelined.

In June, six elite crime intelligence officers were arrested under what appeared to be flimsy charges, despite their success in dismantling drug cartels.

The officers were arrested for “HR violations” while the arrest of their commander, Kumar, over a drug bust worth 200 million rand was quietly ignored.

The question now becomes: Who benefits from these actions? Who benefits from the collapse of crime intelligence in South Africa? And why is there so much resistance to reform within law enforcement?

The answer lies, in part, with a man named Vussy Matala, known as “.

Matala is a key figure in South Africa’s underworld, allegedly operating with impunity through his security company, which has established deep ties with SAPS at multiple levels.

Matala’s goal has been clear: He wants control over South Africa’s police service.

Matala’s influence runs so deep that even after his contract with SAPS was canceled in May 2021, he was able to send messages to those in power, threatening to expose their dirty dealings unless his contract was reinstated.

On May 30th, just 16 days after Matala sent his threatening message, the investigative directorate against corruption (IDC) suddenly took action, and the political killings task team was disbanded.

The team had been investigating Matala, and with their removal, Matala was effectively protected from the scrutiny he so feared.

General Muanazi has publicly stated that Matala is directly involved in the deaths of these three constables.

The officers, who worked in cyber security within crime intelligence, were likely killed because they were getting too close to exposing Matala’s extensive network of corruption and criminal activity.

The deaths of these officers are a grim reflection of what happens when law enforcement is compromised, and when powerful criminal forces manage to infiltrate and neutralize key intelligence units.

The pattern of corruption runs deep.

The government has been unable to prevent Matala’s influence over the police, and his network continues to operate unchecked.

The deaths of Constables Sabia, Matt Lala, and Chinu are a tragic and glaring example of what happens when crime intelligence is systematically destroyed from within.

These three officers had the knowledge and the access to potentially dismantle the criminal networks that Matala runs, but instead, their lives were ended in a manner that raises serious questions about the integrity of South Africa’s policing system.

This case is far from over.

While the official story continues to evolve, the public remains skeptical, demanding answers.

As this story unfolds, the questions about the future of crime intelligence, the role of corruption within SAPS, and the impunity with which criminals like Matala operate will continue to dominate the national conversation.

South Africa faces an uncertain future when it comes to justice, law enforcement, and the fight against organized crime.

The three constables are gone, but the fight they were engaged in continues.

Their deaths may be a tragic moment in a larger narrative of power struggles, corruption, and compromised institutions.

As we wait for the truth to emerge, we must remember that the battle for justice is far from over.

The walls of corruption may be high, but they are not impenetrable.